See a list of chapters.

Sekhet

Goddess of the Cats

Excerpted from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti, 1909, 1924

IN THE TEMPLE OF THE OGRESS

meeting the lion goddess Sekhet (Sekhmet)

This evening, at the hour in which the

light of the Sun begins to turn to rose, I make my way along one of

the magnificent roads of the town-mummy. A road through the vast chaos of ruins that goes off

at a right angle to the line of the temples of Amen, and, losing

itself more or less in the sands, leads at length to a sacred lake.

This particular

road was begun three thousand four hundred years ago by a beautiful New Kingdom queen called Makeri, and in the following centuries a number of

kings continued its construction. It was ornamented with pylons of a

superb massiveness. Pylons are monumental walls, in the form of a

trapezium with a wide base and a door at the center, which

the Egyptians used to place at either side of their porticoes and long

avenues--as well as by colossal statues and interminable rows of rams,

larger than buffalo, crouched on pedestals.

At the first pylon I have to make a detour. The walls are so ruinous that

their blocks, fallen down on all sides, have closed the passage. Here

used to watch, on right and left, two upright giants of red granite

from Syene. Long ago in times no longer precisely known they were

broken off, both of them, at the height of the loins. But their

muscular legs have kept their proud, marching attitude, and each in

one of the armless hands clenches passionately the emblem of eternal life.

And this Syenite granite is so hard that time has not altered it in

the least. In the midst of the confusion of stones the thighs of these

mutilated giants gleam as if they had been polished yesterday.

Farther on we come upon the second pylon, foundered also, before

which stands a row of Pharaohs.

On every side the overthrown blocks display their utter confusion of

gigantic things. In their midst, the sand continues patiently to

bury them. And here now the third pylon, flanked by two

marching giants who have neither head nor shoulders. And the road,

marked majestically still by the debris, continues to lead towards the

desert.

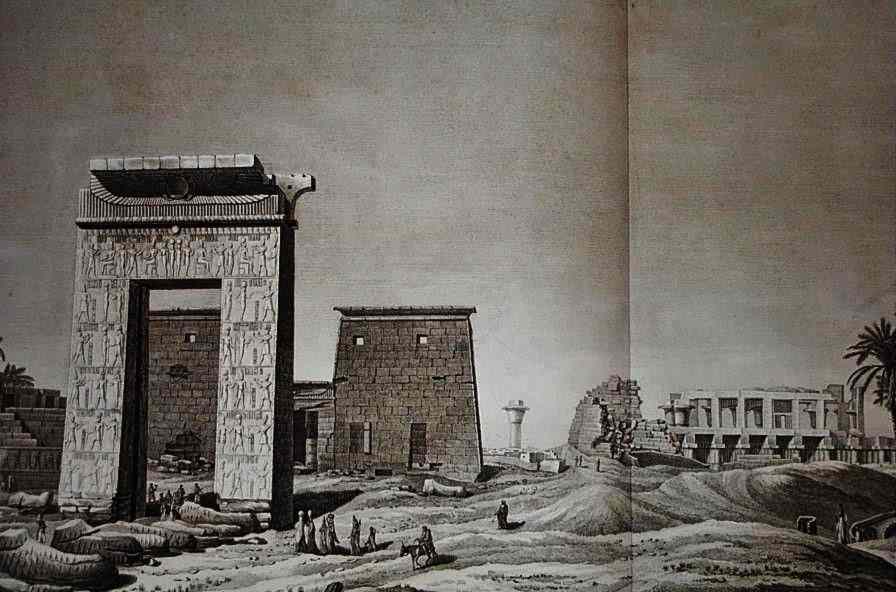

The South entrance of the Temple of Karnac

From "la Description de l'Egypte".

And then the fourth and last pylon, which seems at first sight to mark

the extremity of the ruins, the beginning of the desert nothingness.

Time-worn and uncrowned, but stiff and upright still, it seems to be

set there so solidly that nothing could ever overthrow it. The two

colossal statues which guard the exit on the right and left are seated on

thrones. One, that on the eastern side, has almost disappeared. But

the other stands out entire and white with the whiteness of marble,

against the brown-colored background of the enormous wall. His face alone has been mutilated, and he

preserves still his imperious chin, his ears, his Sphinx's headgear.

One might almost see his meditative expression before this deployment

of the vast solitude which seems to begin at his feet.

Here, however, was only the boundary of the quarters of the God Amen.

The boundary of Thebes was much farther on, and the avenue which will

lead me directly to the home of the cat-headed goddesses extends

farther still, to the old gates of the town. You can scarcely

distinguish the road between the double row of sphinxes all broken and

well-nigh buried.

The day falls, and the dust of Egypt, in accordance with its

invariable practice every evening, begins to resemble in the distance

a powder of gold. I look behind me from time to time at the giant who

watches me, seated at the foot of his pylon on which the history of a

Pharaoh is carved. Above him and above his

wall, which grows each minute more rose-colored, I see, gradually

mounting in proportion as I move away from it, the great mass of the

palaces of the center of Karnak. The hypostyle hall, the halls of Thothmes and

the obelisks, all the entangled cluster of those things at once so

grand and so dead, these are things which have never been equalled on Earth.

All this is now a long way behind me, but the air is so clear, the

outlines remain so sharp, that the illusion is rather that the temples

and the pylons grow smaller, lower themselves and sink into the earth.

The white giant who follows me always with his sightless stare is now

reduced to the proportions of a simple human dreamer. His attitude

moreover has not the rigid hieratic aspect of the other Theban

statues. With his hands upon his knees he looks like a mere ordinary

mortal who had stopped to reflect. (Statue of Amenophis III)

I have known him for many days--

for many days and many nights. With his whiteness and the

transparency of these Egyptian nights, I have seen him often outlined

in the distance. Under the dim light of the stars he becomes a great phantom in

his contemplative pose. And I feel myself obsessed now by the

continuance of his attitude at this entrance of the ruins. I, who shall

pass without a morrow from Thebes and even from the Earth - even as we

all pass.

Before conscious life was vouchsafed to me the Phantom was there, had

been there since times which make you shudder to think upon. For three

and thirty centuries, or thereabouts, the eyes of myriads of unknown

men and women who have gone before me, saw him just as I see him now.

Tranquil and white, he remained in this same place, seated before this same

threshold, with his head a little bent, and his pervading air of

thought.

I make my way without hastening, having always a tendency to stop and

look behind me, to watch the silent heap of palaces and the white

dreamer, which now are all illuminated with a last Bengal fire in the

daily setting of the sun.

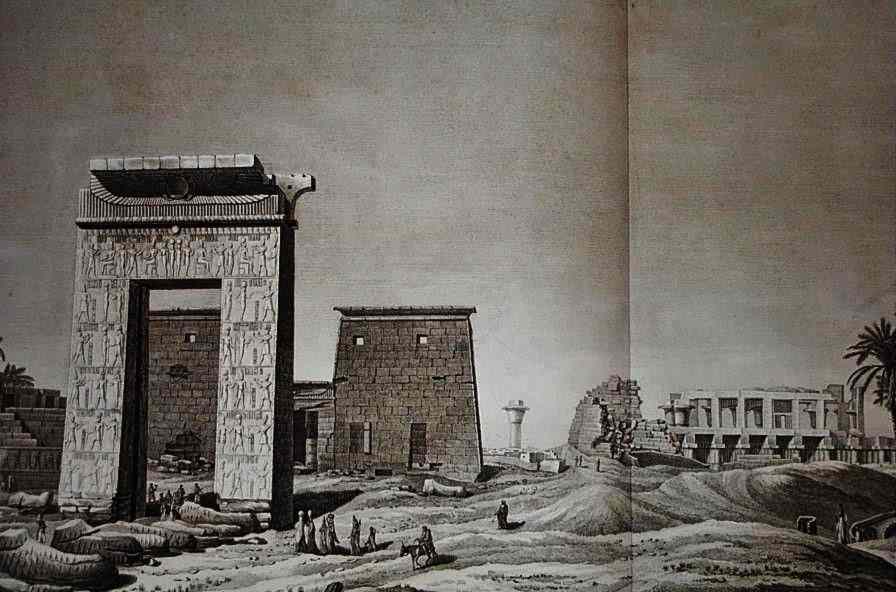

The Temple of Mut at Karnak

by Otto Georgi, 1850.

The hour is already twilight when I reach the goddesses. Their domain is so destroyed that the sands had succeeded in covering and hiding it for centuries. But it has lately been exhumed. There remain of it now only some fragments of columns, aligned in

multiple rows in a vast extent of desert, broken and fallen stones and

debris.

I walk on without stopping, and at length reach the sacred

lake on the margin of which the great cats are seated in eternal

council, each one on her throne. The lake, dug by order of the

Pharaoh, is in the form of a crescent. Some

marsh birds that were about to retire for the night now traverse its

mournful sleeping water. Its borders, which have known the utmost of

magnificence, have become mere heaps of ruins on which nothing grows.

And what one sees beyond, what the attentive goddesses themselves

regard, is the empty desolate plain, on which some few poor fields of

grain mingle in this twilight hour with the sad infinitude of the

sands. And the whole is bounded on the horizon by the chain, still a

little rose-colored, of the rugged mountains of Arabia.

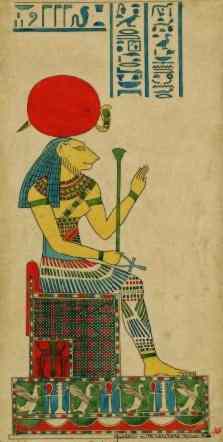

Sekhmet. Wall relief at Kom Ombo.

Photograph by Gerard Ducher, CreativeCommons.

They are there, the cats, or, to speak more exactly, the lionesses,

for cats would not have those short ears, or those cruel chins,

thickened by tufts of beard. All of black granite, images of Sekhet (Sekhmet or Sachmet), who was the Goddess of War, and in her hours the Goddess of Lust. They have the slender body of a woman, which makes more terrible the

great feline head surmounted by its high bonnet. Eight or ten, or

perhaps more, they are more disquieting in that they are so numerous

and so alike.

They are not gigantic, as one might have expected, but

of ordinary human stature. They would be easy therefore to carry away, or to

destroy, and that again, if one reflects, augments the singular

impression they cause. When so many colossal figures lie in pieces on

the ground, how comes it that they, little people seated so tranquilly

on their chairs, have contrived to remain intact, during the passing

of the three and thirty centuries of the world's history?

The passage of the marsh birds, which for a moment disturbed the clear

mirror of the lake, has ceased. Around the goddesses nothing moves and

the customary infinite silence envelops them as at the fall of every

night. They dwell indeed in such a forlorn corner of the ruins! Who,

to be sure, even in broad daylight, would think of visiting them?

Down there in the west a trailing cloud of dust indicates the

departure of the tourists, who had flocked to the temple of Amen, and

now hasten back to Luxor. The

ground here is so felted with sand that in the distance we cannot hear

the rolling of their carriages. But the knowledge that they are gone

renders more intimate the interview with these numerous and identical

goddesses, who little by little have been draped in shadow. Their

seats turn their backs to the temples of Karnak, which now begin to be

bathed in violet waves and seem to sink towards the horizon. They seem to lose

each minute something of their importance before the sovereignty of

the night.

And the black goddesses, with their lioness' heads and tall headgear--

sit there with their hands upon their knees, with eyes fixed since

the beginning of the ages. The goddesses continue to regard that desert, which now is only a confused immensity of a bluish

ashy-grey.

The fancy seizes you that they are possessed of a kind

of life, which has come to them after long waiting, by virtue of that

expression which they have worn on their faces so long, Oh! so long.

Plan of the Temple of Mut at Karnac,

by Erbkam.

Beyond, at the other extremity of the ruins, there is a sister of

these goddesses, taller than they, a great Sekhet, whom in these parts

men call the Ogress, and who dwells alone and upright, ambushed in a

narrow temple. Among the fellahs and the Bedouins of the

neighborhood she enjoys a very bad reputation, it being her custom of

nights to issue from her temple, and devour men. None of them

would willingly venture near her dwelling at this late hour. But

instead of returning to Luxor, like the good people whose carriages

have just departed, I rather choose to pay her a visit.

Her dwelling is some distance away, and I shall not reach it till the

dead of night. First of all I have to retrace my steps, to return along the whole

avenue of rams, to pass again by the feet of the white giant. He has

already assumed his phantomlike appearance, while the violet waves

that bathed the town-mummy thicken and turn to a greyish-blue. And

then, leaving behind me the pylons guarded by the broken giants, I

thread my way among the palaces of the center.

It is among these palaces that I encounter for good and all the night,

with the first cries of the owls and ospreys. It is still warm there,

on account of the heat stored by the stones during the day, but one

feels nevertheless that the air is freezing.

At a crossing a tall human figure looms up, draped in black and armed

with a baton. It is a roving Bedouin, one of the guards, and this more

or less is the dialogue exchanged between us (freely and succinctly

translated):

At a crossing a tall human figure looms up, draped in black and armed

with a baton. It is a roving Bedouin, one of the guards, and this more

or less is the dialogue exchanged between us (freely and succinctly

translated):

"Your permit, sir."

"Here it is."

(Here we combine our efforts to illuminate the said permit by the light of a match.)

"Good, I will go with you."

"No. I beg of you."

"Yes, I had better. Where are you going?"

"Beyond, to the temple of that lady ... you know, who is great and powerful and has a face like a lioness."

"Ah! . . . Yes, I think I understand that you would prefer to go

alone." (Here the intonation becomes pleading.) "But you are a kind

gentleman and will not forget the poor Bedouin all the same?"

He goes on his way. On leaving the palaces I have still to traverse an

extent of uncultivated country, where a veritable cold seizes me.

Above my head are no longer the heavy suspended stones, but the far-off

expanse of the blue night sky--where are shining now myriads upon

myriads of stars.

For the Thebans of old this beautiful vault,

scintillating always with its powder of diamonds, shed no doubt only

serenity upon their souls. But for us, it is on the

contrary the field of the great fear, which, out of pity, it would

have been better if we had never been able to see. The incommensurable

black void, where the worlds in their frenzied whirling precipitate

themselves like rain, crash into and annihilate one another, only to

be renewed for fresh eternities.

All this is seen too vividly, the horror of it becomes intolerable, on

a clear night like this, in a place so silent and littered so with

ruins. More and more the cold penetrates you--the mournful cold of the

sidereal spheres from which nothing now seems to protect you, so

rarefied--almost non-existent--does the limpid atmosphere appear. The gravel, the poor dried herbs, that crackle under foot, give the

illusion of the crunching noise we know at home on winter nights when

the frost is on the ground.

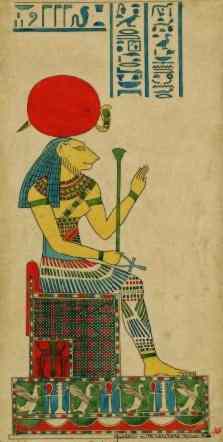

Temple of Ptah at Karnak, 1911.

Called by the local people the temple of the Ogress.

I approach at length the temple of the Ogress. These stones which now

appear, whitish in the night, this secret-looking dwelling near the

boundary wall of Karnak, proclaim the spot. At such an hour

as this it has an evil aspect. You pass Ptolemaic columns, little vestibules,

little courtyards where a dim blue light enables you to find your way.

Nothing moves, not even the flight of a night bird. An absolute

silence, magnified awfully by the presence of the desert which you

feel encompasses you beyond these walls.

Beyond, at the bottom,

three chambers made of massive stone, each with its separate entrance.

I know that the first two are empty. It is in the third that the

Ogress dwells, unless, indeed, she has already set out upon her

nocturnal hunt for human flesh. Pitch darkness reigns within and I

have to grope my way. Quickly I light a match. Yes, there she is

indeed, alone and upright, almost part of the end wall on which my

little light makes the horrible shadow of her head dance.

The match

goes out. Irreverently I light many more under her chin, under that

heavy, man-eating jaw. In very sooth, she is terrifying. Of black

granite--like her sisters seated on the margin of the mournful lake--

but much taller than they, from six to eight feet in height. She has a

woman's body, exquisitely slim and young, with the breasts of a

virgin. Very chaste in attitude, she holds in her hand a long-stemmed

lotus flower. By a contrast that nonplusses and paralyses you the

delicate shoulders support the monstrosity of a huge lioness' head.

The lappets of her bonnet fall on either side of her ears almost down

to her breast. Surmounting the bonnet is a large moon disc. Her dead stare gives to the

ferocity of her visage something unreasoning and fatal. She is an

irresponsible ogress, without pity as without pleasure, devouring

after the manner of Nature and of Time. And it was so perhaps that she

was understood by the initiated of ancient Egypt, who symbolised

everything for the people in the figures of gods.

Sekhmet carved in granite.

Pharaoh Amenhotep III had hundreds of similar statues made.

These two are in the Berlin Museum.

photo: Magnus Manske, 2005. License.

In the dark retreat, enclosed with defaced stones, in the little

temple where she stands, alone, upright and grand, one is

necessarily quite close to her. In touching her, at night, you are

astonished to find that she is less cold than the air. She becomes

somebody, and the intolerable dead stare seems to weigh you down.

During the visit one thinks involuntarily of the

surroundings, of these ruins in the desert, of long lost and forgotten dreams, of the cold beneath the stars. And, now, that summation

of doubt and despair is confirmed by the meeting with

this divinity-symbol, which awaits you at the end of the journey. A rigid horror of granite, with

an implacable smile and a devouring jaw.

Excerpted from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti, 1909, 1924

NEXT CHAPTER

Sacred to Pasht by Edwin Long

Both bronze cats are mummy masks from the Ptolemaic era,

now in the British Museum. Photographs from Egyptarchive.

Countless beautiful 19th century images of ancient Egypt

and 75 pages of architecture, art and mystery

are linked from the library page:

The Egyptian Secrets Library

At a crossing a tall human figure looms up, draped in black and armed

with a baton. It is a roving Bedouin, one of the guards, and this more

or less is the dialogue exchanged between us (freely and succinctly

translated):

At a crossing a tall human figure looms up, draped in black and armed

with a baton. It is a roving Bedouin, one of the guards, and this more

or less is the dialogue exchanged between us (freely and succinctly

translated):