Man in all times and places has speculated on the nature and origin of the world, and connected such questions with his theology. In ancient Egypt there were several theories of creation, with various elaborated forms. There were two principal views of the formation of the earth:

(1) That it had been brought into being by the word of a god, who when he uttered any name caused the object thereby to exist. Thoth is the principal creator by this means and this idea probably belongs to a period soon after the age of the animal gods.

(2) The other view is that Ptah framed the world as an artificer, with the aid of eight Khnumu, or earth-gnomes. This belongs to the theology of the abstract gods. The people seem to have been content with the eternity of matter, and only personified nature when they described space, Shu, as separating the sky, Nut, from the earth, Seb. This is akin to the separation of chaos into sky and sea in Genesis.

Before dealing with the special varieties of the Egyptians' belief in gods, it is best to try to avoid a misunderstanding of their whole conception of the supernatural. The term "god" has come to imply to our minds a specialized group of attributes. It would be difficult to throw our ideas back into the more remote conceptions we also call "god". The ancient deities were beneficent and powerful. If we use the word "god" for such conceptions, it must always be with the reservation that the word has now a very different meaning.

When we reach the age of written language we find the person is denoted by the khu between the arms of the ka. From later writings it is seen that the khu is applied to a spirit of man, while the ka is not the body but the activities of sense and perception. Thus, in the earliest age of documents, two entities were believed to vitalize the body.

The KA is more frequently named than any other part, all funeral offerings were made for the KA. It is said that if opportunities of satisfaction in life were missed it is grievous to the ka, and that the ka must not be annoyed needlessly. It was more than perception, and it included all that we might call consciousness. Perhaps we may grasp the ka best as the "self," with the same variety of meaning that we have in our own word. The ka was represented as a human being following after the man. It was born at the same time as the man, but persisted after death and lived in and about the tomb. It could act and visit other kas after death, but it could not resist the least touch of physical force. It was always represented by two upraised arms, the active parts of the person. All objects likewise had their kas, comparable to the human ka, and among these the ka lived. This view leads closely to the world of ideas permeating the material world in later philosophy.

The KHU is pictured as a crested bird, which has the meaning of "glorious" or "shining" in ordinary use. It refers to a less material conception than the ka, and may be called the intelligence or spirit.

The KHAT is the material body of man which was the vehicle of the KA, and inhabited by the KHU.

The BA or BAI belongs to a different pneumatology. It is the soul apart from the body, pictured as a human-headed bird. The conception probably arose from the white owls, with round heads and every human expression, which frequent the tombs flying noiselessly to and fro. The ba required food and drink. It thus overlaps the scope of the ka, and probably belongs to a different tradition.

The sahu or mummy is associated particularly with the ba and the ba bird is often shown as resting on the mummy or seeking to re-enter it.

The khaybet was the shadow of a man. The shadow was of great importance in early ideas.

The sekhem was the force or ruling power of man, but is rarely mentioned.

The ab is the will and intentions, symbolised by the heart. It was often used in phrases such as a man being "in the heart of his lord," "wideness of heart" for satisfaction, "washing of the heart" for giving vent to temper.

The hati is the physical heart, the chief organ of the body.

The ran is the name which was essential to man, as also to inanimate things. Without a name nothing really existed. Knowledge of the name gave power over its owner. A great myth turns on Isis obtaining the name of Ra by stratagem, and thus getting the two eyes of Ra--the sun and moon--for her son Horus. In ancient times the knowledge of the real name of a person was carefully guarded, and often secondary names were used for secular purposes. It was usual for Egyptians to have a "great name" and a "little name". The great name is often compounded with that of a god or a king, and was very probably reserved for religious purposes, as it is only found on religious and funerary monuments.

We must not suppose that all of these parts of the person were equally important, or were believed in simultaneously. The ka, khu, and khat seem to form one group; the ba and sehu belong to another; the ab, hati, and sekhem, heart and will, are hardly more than metaphors; the khaybet is a later idea which probably belongs to the system of animism and witchcraft, where the shadow gave a hold upon the man. The ran, name, belongs partly to the same system, but also is the germ of the later philosophy of idea.

The purpose of religion to the Egyptian was to secure the favor of the god. There is but little trace of negative prayer to avert evils or deprecate evil influences, but rather of positive prayer for concrete favors. On the part of kings this is usually offering to provide temples and services to the god in return for material prosperity. The Egyptian had no confession to make of sin or wrong, and had no thought of pardon. In the judgment he boldly averred that he was free of the forty-two sins that might prevent his entry into the kingdom of Osiris. If he failed to establish his innocence in the weighing of his heart there was no other plea. He was consumed by fire and by a hippopotamus, and no hope remained for him.

The worship of animals has been known in many countries, it usually moves into more human forms as cities develop. In Egypt animal dieties were maintained throughout the civilization. The mixture of such a primitive system with more elevated beliefs seemed strange to the Greeks. The original motive was a kinship of animals with man, much like that underlying the system of totems. Each place or tribe had its sacred species that was linked with the tribe. The life of the species was carefully preserved, excepting in the one selected for worship, which after a given time was killed and sacramentally eaten by the tribe. This was certainly the case with the bull at Memphis and the ram at Thebes. The whole species was sacred, penalties for killing any animal of the species were severe. The Egyptians buried and even mummifed every example they could find of their chosen species in endless caves.

In prehistoric times the serpent was sacred, images of the coiled serpent were hung in the house and worn as an amulet. In historic times a figure of the agathodemon serpent was placed in a temple of Amenhotep III at Benha. In the first dynasty the serpent was figured in pottery, as a defender around the hearth. The hawk also appears in many pre-dynastic figures, both worn on the person and carried as standards. The lion is found both in life-size temple art, lesser objects of worship, and personal amulets. The scorpion was similarly honored in the prehistoric ages.

It is difficult to separate now between animals which were worshipped quite independently, and those which were associated as emblems of anthropomorphic gods. Probably both classes of animals were sacred at a remote time, and the connection with the human form came later. The ideas connected with the animals were those of their most prominent characteristics. It appears that it was for the sake of the character that each animal was worshipped.

The baboon was regarded as the emblem of Tahuti, the god of wisdom. The serious expression and human ways of large baboons are an obvious cause for their being regarded as the wisest of animals. Tahuti is represented as a baboon from the first dynasty down to late times, and four baboons were sacred in his temple at Hemmopolis. These four baboons were often portrayed as adoring the sun; this idea is due to their habit of chattering at sunrise. The baboon is also connected to Thoth. (Those at right are from the base of an Oblisk)

The lioness appears in the compound figures of the goddesses Sekhet, Bast, Mahes, and Tefnut. In the form of Sekhet the lioness is the destructive power of Ra, the sun. It is Sekhet who, in the legend, destroys mankind from Herakleopolis to Heliopolis at the bidding of Ra. The other lioness goddesses are probably likewise destructive or hunting deities. The lesser felines also appear. The cheetah and serval are sacred to Hathor in Sinai, the small cats are sacred to Bast, especially at Speos Artemidos and Bubastis.

The bull was sacred in many places, and his worship underlay that of the human gods, who were said to be incarnated in him. The idea is that of the fighting power, as when the king is figured as a bull trampling on his enemies, and the reproductive power, as in the title of the self-renewing gods, "bull of his mother". The most renowned was the Hapi or Apis bull of Memphis, in whom Ptah was said to be incarnate and who was Osirified and became the Osir-hapi. Thus appears to have originated the great Ptolemaic god Serapis, as certainly the mausoleum of the bulls at Saqqara was the Serapeum known to the Greeks. Another bull of a more massive breed was the Ur-mer or Mnevis of Heliopolis, in whom Ra was incarnate. A third bull was Bakh or Bakis of Hermonthis the incarnation of Mentu. And a fourth bull, Kan-nub or Kanobos, was worshipped at the city of that name. The cow was identified with Hathor, who appears with cow's ears and horns, and who is probably the cow-goddess Ashtaroth or Istar of Asia. Isis, as identified with Hathor, is also joined in this connection.

The ram was also worshipped as a procreative god. At Mendes in the Delta the ram is identified with Osiris, at Herakleopolis identified with Hershefi, at Thebes as Amon, and at the Philae Cataract as Khnumu the creator. The association of the ram with Amon was strongly held by the Ethiopians of Kush and Meroe. In the Greek tale of Nektanebo, the last Pharaoh, he by magic visited Olympias and become the father of Alexander. It is said that he came as the incarnation of Amon, wearing a ram's skin.

The hippopotamus was the goddess Ta-urt, "the great one," the patroness of pregnancy, who is never shown in any other form. Rarely this animal appears as the emblem of the god Set.

The jackal haunted the cemeteries on the edge of the desert, and so came to be the guardian of the dead, and identified with Anubis, the god of departing souls. Another aspect of the jackal was as the maker of tracks in the desert. Jackal packs use the best trails, avoiding the valleys and precipices, so the animal was known as Up-uat, "the opener of ways". The jackal showed the way for the dead across the western desert. Species of dogs were held sacred and mummified.

The hawk was the principal sacred bird, and was identified with Horus and Ra, the sun-god. It was mainly worshipped at Edfu and Hierakonpolis. The souls of kings were supposed to fly up to heaven in the form of hawks, perhaps due to the kingship originating in the hawk district in upper Egypt. Seker, the god of the dead, appears as a mummified hawk. The mummy hawk is also Sopdu, the god of the east.

The vulture was the emblem of maternity, as they were supposed to care especially well for their young. She is identified with Mut, the mother goddess of Thebes. The queen-mothers wear vulture head-dresses, the vulture is shown hovering over kings to protect them, and a row of spread-out vultures are painted on the roofs of tomb passages. The ibis was identified with Tahuti, the god of Hermopolis and with Thoth. The goose is connected with Amon of Thebes.

The crocodile was worshipped in the Fayum, where it frequented the marshy regions of the great lake. It was identified with Osiris as the western god of the dead. The crocodile was also worshipped at Onuphis. At Nubti or Ombos (Kom Ombo) it was identified with Set, and held sacred.

The cobra serpent was sacred from the earliest times to the present day. It was never identified with any of the great deities, but three goddesses appear in serpent form: Uazet, the Delta goddess of Buto; Mert-seger, "the lover of silence," the goddess of the Theban necropolis; and Rannut, the harvest goddess. The memory of great pythons of prehistoric days appears in the immense serpent Agap of the underworld in later mythology. The serpent has also been a popular object of worship apart from specific gods. We have already noted it on prehistoric amulets, and coiled round the hearths of the early dynasties. Serpents were mummified, and in the terra-cotta figures and jewelry of later times the serpent is very prominent. There were usually two represented together, one often with the head of Serapis, the other of Isis, so therefore male and female. Down to modern times a serpent is worshipped at Sheykh Heridy, and miraculous cures attributed to it.

Various fishes were sacred, as the Oxyrhynkhos, Phagros, Lepidotos, Latos, and others, but they were not identified with gods, and we do not know of their being worshipped. The scorpion was the emblem of the goddess Selk, and is found in prehistoric amulets. Most usually it represents evils, as where Horus is shown overcoming noxious creatures.

Nearly all of the animals which were worshipped had qualities for which they were noted, and in connection with which they were venerated. If the animal worship were due to totemism, or a sense of animal brotherhood in certain tribes, we must also assume that was due to these qualities of the animal. Animal worship arose from the nature of the animals, and each animal came to be associated with the worship of a particular tribe or district.

In a country which has been subjected to so many inflows of various peoples as has Egypt, it is to be expected that there would be a great diversity of deities and a complex and inconsistent theology. There are several principal classes of conceptions of gods. The mixed type of human figures with animal heads is clearly an adaptation of the animal gods to the later conception of human-looking gods.

Another valuable separator lies in the compound names of gods. It is impossible to suppose a people uniting two gods, both of which belonged to them originally. There would be no reason for two similar gods in a single system. We never hear in classical mythology of Hermes-Apollo or Pallas-Artemis, while Zeus is compounded with half of the ancient gods of Asia. So in Egypt, when we find such compounds as Amon-Ra, or Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, we have the certainty that each name is derived from a different people, and that a unifying operation has taken place.

We must beware of reading our modern ideas into the ancient views. As we noted in an earlier part of this chapter, each tribe or locality seems to have had but one god originally. Certainly the more remote the time, the more separate are the gods. Hence to the people of any one district "the god" was a distinctive name for their own god. We find generic descriptions used in place of the god's name, as "lord of heaven," or "mistress of turquoise".

Beside the worship of species of animals, certain animals were combined with the human form. It was almost always the head of the animal which was united to a human body, there are few exceptions, the sphinxes, the Ba. Possibly the combination arose from priests wearing the heads of animals when impersonating the god. The love of symbolism shown in the early carvings makes the union of the ancient sacred animal with the human form in keeping with the views and feelings of the primitive Egyptians. Many of these composite gods never emerged from their animal connection.

Seker was a Memphite god of the dead, independent of the worship of Osiris and of Ptah, for he was combined with them as Ptah-Seker-Osiris. As he maintained a place there in the face of the great worship of Ptah, he was probably an older god, and this is indicated by his having an entirely animal form down to a late date. The sacred bark of Seker bore his figure as that of a mummified hawk; and along the boat is a row of hawks which probably are the spirits of deceased kings who have joined Seker in his journey to the world of the dead.

As there are often two allied forms of the same root, one written with k and the other with g, it seems probable that Seker, the funeral god of Memphis, is allied to Mert Seger (lover of silence). She was the funeral god of Thebes, and was usually shown as a serpent. From being only known in animal form, and unconnected with any of the elaborated theology, it seems this goddess is a primitive deity of the dead. It appears, then, that the gods of the great cemeteries were known as Silence and the Lover of Silence, and both come down from the age of animal deities. Seker in late times changed into a hawk-headed human figure.

Two important deities of early times were Nekhebt (Left), the vulture goddess of the southern kingdom, centered at Hierakonpolis, and Uazet, the serpent goddess of the northern kingdom, centred at Buto. These appear in all ages as the emblems of the two kingdoms, frequently as supporters on either side of the royal names. In later times they appear as human goddesses crowning the king.

Khnumu, the creator, was the great god of the cataract. He is shown as making man upon the potter's wheel. He must belong to a different source from that of Ptah or Ra, and was the creative principle in the period of animal gods, as he is almost always shown with the head of a ram. He was popular down to late times, where amulets of his figure are often found.

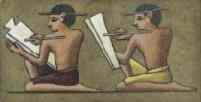

Tahuti, or Thoth (Thôth), was the god of writing and

learning, and was the chief deity of Hermopolis. He almost always has

the head of an ibis, the bird sacred to him. The baboon is also a

frequent emblem of his, but he is never figured with the baboon head.

The ibis appears standing upon a shrine as early as on a tablet of

Menes (first dynasty). Thôth is the recorder in scenes of the judgment, and he

appears down to Roman times as the patron of scribes. Eighteenth

dynasty pharaohs incorporated his name as Thôthmes, "born of Thôth,"

owing to their Hermopolis origin.

Skhmet is the lion goddess, who represents the fierceness of the sun's heat. She appears in the myth of the destruction of mankind slaughtering the enemies of Ra. Her only form is with the head of a lioness.

She blends imperceptibly with Bastet, who has the head of a cat. She was the goddess of Pa-bast or Bubastis. In her honor immense festivals were held there. Her name is found from the beginning of pyramid times, but her main period of popularity was that of the Shisaks who ruled from Bubastis. In later times images of her were very frequent used as amulets. It is possible that this feline goddess, whose foreign origin is acknowledged, was the female form of the god Bes, who is dressed in a lion's skin, and also came in from the east.

Mentu was the hawk-god of Erment, south of Thebes, who became in the eighteenth to twentieth dynasties the god of war. He appears with the hawk head, or sometimes as a hawk-headed sphinx; and he became confused with Ra and with Amon.

Heqt, the goddess symbolised by the frog, was the patron of birth, and assisted in the infancy of the kings. She was a popular and general deity not mainly associated with particular places.

Hershefi was the ram-headed god of Herakleopolis, but is never found outside of that region.

Three animal-headed gods became associated with the great Osiris group of human gods. Set or Setesh was the god of the prehistoric inhabitants before the coming of Horus. He is always shown with the head of a fabulous animal, having upright square ears and a long nose. When in entirely animal form he has a long upright tail. A dog-like animal is the earliest type, as in the second dynasty, but later the human form with an animal head prevailed. His worship underwent great fluctuations. At first he was the great god of all Egypt, but his worshippers were gradually driven out by the followers of Horus, as described in a semi-mythical history. Then he appears strongly in the second dynasty, the last king of which united the worship of Set and Horus. After suppression he appears again in favor in the early eighteenth dynasty, and even gave the name to Seti I and II of the nineteenth dynasty.

Anpu or Anubis was originally the jackal guardian of the cemetery, and the leader of the dead in the other world. Nearly all the early funeral formula mention Anpu on his hill, or Anpu lord of the underworld. As the patron of the dead he naturally took a place in the myth of Osiris, the god of the dead, and appears leading the soul into the judgment of Osiris.

Horus was the hawk-god of upper Egypt, especially of Edfu and Hierakonpolis. Though originally an independent god, and kept apart as Hor-ur, "Horus the elder" throughout later times, yet he was early mingled with the Osiris myth, probably as the victor over Set who was also the enemy of Osiris. He is sometimes entirely in hawk form, more usually with a hawk's head. In later times he appears as the infant son of Isis, entirely human in form. His special function is that of overcoming evil, in the earliest days the conqueror of Set, later as the subduer of noxious animals, and lastly, in Roman times, as a hawk-headed warrior on horseback slaying a dragon, thus passing into the type of St. George (note the similarity of the names).

There are three divisions of this class, the Osiris family, the Amon family, and the goddess Neit.

Osiris -- Asar or Asir--is the most familiar figure of the pantheon, but it is from mainly late sources that we have the myth. His worship was so much adapted to harmonize with other ideas that care is needed to trace his true position. The Osiride portions of the Book of the Dead are certainly very early, and precede the solar portions, though both views were already mingled in the pyramid texts. It is certain that Osiris worship reaches back to the prehistoric age.

In the earliest tombs offering to Anubis is found, for whom Osiris became substituted in the fifth and sixth dynasties. In the pyramid times we only find that kings are termed Osiris, having undergone their apotheoisis at the sed festival, but in the eighteenth dynasty and onward every justified person was entitled to the term Osiris, as being united with the god. His worship was unknown at Abydos in the earlier temples, though in later times he became the leading deity there.

Thus in all directions the recognition of Osiris continued to increase. This was the gradual triumph of a popular religion over a state religion which had been superimposed upon it.

The earliest phase of Osirism that we can identify is in portions of the Book of the Dead. These assume the kingdom of Osiris, and a judgment preceding admission to the blessed future. The completely human character of Osiris and his family are implied, and there is no trace of animal or nature worship belonging to him.

How far the myth, as recorded in Roman times by Plutarch, can be traced to earlier sources is very uncertain. The main outlines, which may be primitive, are as follows. Osiris was a civilising king of Egypt, who was murdered by his brother Set and seventy-two conspirators. Isis, his wife, found the coffin of Osiris at Byblos in Syria and brought it to Egypt. Set then tore up the body of Osiris and scattered it. Isis sought the fragments, and built a shrine over each of them. Isis and Horus then attacked Set and drove him from Egypt, and finally down the Red Sea.

In other aspects Osiris seems to have been a grain god, and the scattering of his body in Egypt is like the well-known division of the sacrifice to the grain god, and the burial of parts in separate fields to ensure their fertility.

How we are to analyse the formation of the early myths is suggested by the known changes of later times. When two tribes who worshipped different gods fought together and one overcame the other, the god of the conqueror is always considered to have overcome the god of the vanquished. The struggle of Horus and Set is expressly stated on the Temple of Edfu to have been a tribal war, in which the followers of Horus overcame those of Set, established garrisons and forges at various places down the Nile Valley, and finally ousted the Set party from the whole land. We can hardly therefore avoid reading the history of the animosities of the gods as being the struggles of their worshippers.

Osiris worshippers occupied both the Delta and upper Egypt. Fourteen important centers were recognised from the earliest time as the locations of his fragments, which afterwards became the capitals of nomes (countys). These were added to until they numbered forty-two divisions in later ages.

Set was the god of the Asiatic invaders who broke in upon this civilization; and about 7500 B.C., we find material evidences of considerable changes brought in from the Arabian or Semitic side.

The Isis worshippers came from the Delta, where Isis was worshipped at Buto as a virgin goddess, apart from Osiris or Horus. The close of the prehistoric age is marked by a great decline in work and abilities, very likely due to more trouble from Asia.

The dynastic people came down from the district of Edfu and Hierakonpolis, the centers of Horus worship and helped the older inhabitants to drive out the Asiatics.

If we can thus succeed in connecting the archæology of the prehistoric age with the history preserved in the myths it shows that Osiris must have been the national god as early as the beginning of prehistoric culture. His civilizing mission may well have been the introduction of agriculture into the Nile Valley.

The theology of Osiris was at first that of a god of those holy fields in which the souls of the dead enjoyed a future life. There was necessarily some selection to exclude the wicked from such happiness, and Osiris judged each soul whether it were worthy. This judgment became elaborated in detailed scenes, where Isis and Neb-hat stand behind Osiris who is on his throne, Anubis leads in the soul, the heart is placed in the balance, and Thôth stands to weigh it and to record the result. The function of Osiris was the reception and rule of the dead, and we never find him as a god of action or patronizing any of the affairs of life.

Isis -- Aset or Isit--became attached at a very early time to Osiris worship. She appears in later myths as the sister and wife of Osiris, but she always remained on a very different plane to Osiris. Her worship and priesthood were far more popular than those of Osiris, and she appears far more usually in the activities of life. Her union in the Osiris myth by no means blotted out her independent position and importance as a deity.

The establishment of Isis as the mother goddess was the main mode of her importance in later times. Isis as the nursing mother is seldom shown until the twenty-sixth dynasty, then the type continually became more popular, until it outgrew all other religions of the country. In Roman times the mother Isis not only received the devotion of all Egypt, but her worship spread rapidly abroad, like that of Mithra. It became the popular devotion of Italy, and after a change of name she has continued to receive the adoration of a large part of Europe down to the present day.

Nephthys -- Neb-hat was a shadowy double of Isis, reputedly her sister, and always associated with her, she seems to have no other function. Her name, "mistress of the palace," suggests that she was the consort of Osiris at the first, as a necessary but passive complement in the system of his kingdom. When the active Isis worship entered into the renovation of Osiris, Nebhat remained of nominal importance.

Horus -- Heru or Horu has a more complex history than any other Egyptian god. We can discriminate the following ideas:

(a) There was an elder or greater Horus, Hor-ur who was credited with being the brother of Osiris, older than Isis, Set, or Nephthys. He was the god of Letopolis. What connection this god had with the hawk we do not know; often Horus is found written without the hawk, simply as hr, with the meaning of "upper" or "above." This word generally has the determinative of sky, and so means primitively the sky or one belonging to the sky. It is at least possible that there was a sky-god her at Letopolis, and likewise the hawk-god was a sky-god her at Edfu, and hence the mixture of the two deities.

(b) It is always the hawk-headed Horus who wars against Set, and attends on the enthroned Osiris.

(c) The hawk Horus became identified with the sun-god, from this came the winged solar disk as the emblem of Horus of Edfu, and the title of Horus on the horizons--at rising and setting--Hor-emakhti, or Harmakhis.

(d) Another aspect resulting from Horus being the "sky" god, was that the sun and moon were his two eyes. He was Hor-merti, Horus of the two eyes, and the sacred eye of Horus, the uza, became the most usual of all amulets.

(e) Horus, as conqueror of Set, appears as the hawk standing on the sign of gold, nub, nubti was the title of Set, and thus Horus is shown trampling upon Set. This became a usual title of the kings. There are many less important forms of Horus, but the form which outgrew all others in popular estimation was

(f) Hor-pe-khroti, Harpokrates of the Greeks, "Horus the child". As the son of Isis he constantly appears from the nineteenth dynasty onward. One of the earlier of these forms is that of the boy Horus standing upon crocodiles, and grasping scorpions and noxious animals in his hands. This type was a favorite amulet down to Ptolemaic times, and is often found carved in stone to be placed in a house, but was scarcely ever made in other materials or for wear on the person. But the infant Horus with his finger to his lips was the most popular form of all. From the twenty-sixth dynasty down to late Roman times the young Horus was the most prominent subject on the temples and in the homes of the people.

The other main group of human gods was Amon, Mut, and Khonsu of Thebes. Amon was the local god of Karnak, and owed his importance in Egypt to the political rise of his district. The Theban kingdom of the twelfth dynasty spread his fame, the great kings of the eighteenth and nineteenth dynasty ascribed their victories to him. The high priesthood of Amon became a political power which absorbed the state after the twentieth dynasty, and the importance of the god only ceased with the fall of his city.

The original attributes and the origin of the name of Amon are unknown. He became combined with Ra, the sun-god, as Amon-Ra. The supremacy of Amon was for some centuries an article of political faith, and many other gods were merged in him. The queens were the high priestesses of the god, and he was the divine father of their children - the kings were only incarnations of Amon in their relation to the queens.

Mut, the great mother, was the goddess of Thebes, and

hence the consort of Amon. She is often shown as leading and protecting

the kings, and the queens appear in the character of this goddess.

Little is known about her otherwise.

(Right) Mut, in the Luxor Museum, Egyptarchive.

Khonsu is a youthful god in the Theban system, the son of Amon and Mut. He is closely parallel to Thôth as a god of time, as a moon god, and of science, "the executor of plans". A large temple was dedicated to him at Karnak, but otherwise he was not of religious importance.

Neit was a goddess of the Libyan people, but her worship was firmly implanted by them in Egypt. She was a goddess of hunting and of weaving, the two arts of a nomadic people. Her emblem was a distaff with two crossed arrows, and her name was written with a figure of a weaver's shuttle. She was adored in the first dynasty, when the name Merneit, "loved by Neit," occurs; and her priesthood was one of the most common in the pyramid period. She was almost lost to sight during some thousands of years, but she became the state goddess of the twenty-sixth dynasty when the Libyans set up their capital in her city of Sais. In later times she again disappears from customary religion.

The gods which personify the sun and sky stand apart in their essential idea from those already described, although they were largely mixed and combined with the other gods. Ra was the great sun-god to whom every king pledged himself by adopting on his accession a motto-title embodying the god's name: Ra-men-kau, "Ra established the kas"; Ra-sehotep-ab, "Ra satisfied the heart"; Ra-neb-maat, "Ra is the lord of truth". These titles were those by which the king was best known. This began in the fourth dynasty, and was established when fifth dynasty pharaohs were called sons of Ra. Every later king had the title "Son of Ra" before his name.

The obelisk was the emblem of Ra, and in the fifth dynasty a great sun temple was built in his honor at Abusir, followed also by others. Heliopolis was the center of his worship, where Senusert I, in the twelfth dynasty, rebuilt the temple. Thutmose III of the Eighteenth Dynasty, erected two obelisks c. 1450 BC, one of which is still standing at Heliopolis, (seen at left.) and one is now in New York City (above). But Ra was preceded there by another sun-god, Atmu, who was the true god of the nome. Ra, though worshipped throughout the land, was not the original god of any city. In Heliopolis he was attached to Atmu, at Thebes attached to Amen.

These facts point to Ra having been introduced into Egypt by a conquering people. There are many suggestions that the Ra worshippers came in from Asia, and established their rule at Heliopolis. The title of the ruler of that place was the heq, a semitic title. The heq sceptre was the sacred treasure of the temple. The "spirits of Heliopolis" were specially honored, an idea more Babylonian than Egyptian. This city was a center of literary learning and of theologic theorizing which was unknown elsewhere in Egypt, but familiar in Mesopotamia.

A conical stone was the embodiment of the god at Heliopolis, as in Syria. On, the native name of Heliopolis, occurs twice in Syria, as well as other cities named Heliopolis there in later times. The view of an early Semitic principate of Heliopolis, before the dynastic age, would unify all of these facts, and the advance of Ra worship in the fifth dynasty would be due to a revival of the influence of the eastern Delta at that time.

The form of Ra most free from mixture is that of the disk of the sun, sometimes figured between two hills at rising, sometimes between two wings, sometimes in the boat in which it floated on the celestial ocean across the sky. The winged disk has almost always two cobra serpents attached to it, and often the ram's horns of Amun.

This disk form is placed over the head of the hawk and by the disk resting on the hawk-headed man, one of the most usual types of Ra. The god is but seldom shown as being purely human, except when identified with other gods, such as Atmu, Horus, or Amon.

The worship of Ra outshone all others in the nineteenth dynasty. United to the god of Thebes as Amon-Ra, he became "king of the gods". The view that the soul joined Ra in his journey through the hours of the night absorbed all other views, which only became sections of this whole.

Atmu (Tum) was the original god of Heliopolis and the east Delta side, round to the gulf of Suez. How far his nature as the setting sun was the result of his being identified with Ra is not clear. It may be that the introduction of Ra led to his being unified with him.

Khepera has no local importance, but is named as the morning sun. He was worshipped about the time of the nineteenth dynasty.

Aten was a conception of the sun entirely different from Ra. No human or animal form was ever attached to it. The adoration of the physical power and action of the sun was the sole devotion. So far as we can trace, it was a worship entirely apart and different from every other type of religion in Egypt. It can be called a scientific conception of the source of all life and power upon earth.

The Aten was worshiped exclusive of all others, and claimed universality. There are traces of it shortly before Amenhotep III. He showed some devotion to it, and it was his son who took the name of Akhenaten, "the glory of the Aten," and tried to enforce this as the sole worship of Egypt. But it fell soon after his death, and is lost in the next dynasty.

The sun is represented as radiating its beams on all things, every beam ends in a hand which imparts life and power to the king and to all else. In the hymn to the Aten the universal scope of this power is proclaimed as the source of all life and action, and every land and people are subject to it. No such grand theology had ever appeared in the world before, so far as we know. It is the forerunner of the later monotheist religions, while it is even more abstract and impersonal, and may well rank as a scientific theism. Akhenaten and Nefertiti

Anher was the local god of Thinis in upper Egypt, and Sebennytos in the Delta, a human sun-god. His name is a mere epithet, "he who goes in heaven", and it may well be that this was only a title of Ra, who was thus worshipped at these places.

Sopdu was the god of the eastern desert, he was identified with the cone of glowing zodiacal light which precedes the sunrise. His emblem was a mummified hawk, or a human figure.

Nut, the embodiment of heaven, is shown as a female figure dotted over with stars. She was not worshipped nor did she belong to any one place, but was a cosmogonic idea.

Seb, the embodiment of the earth, is pictured as lying on the ground while Nut bends over him. He was the "prince of the gods," the power that went before all the later gods. He is rarely mentioned, and no temples were dedicated to him.

Shu was the god of space, who lifted up Nut from off the body of Seb. He was often represented, especially in late amulets. Possibly it was believed that he would likewise raise up the body of the deceased from earth to heaven. His figure is entirely human, and he kneels on one knee with both hands lifted above his head. He was regarded as the father of Seb, the earth having been formed from space or chaos. His emblem was the ostrich feather, the lightest and most voluminous object.

Hapi, the Nile, must also be placed with nature-gods. He is pictured as a man, or two men for the upper and lower Niles, holding a tray of produce of the land. He has large female breasts as the nourisher of the valley. A favorite group consists of the two Nile figures tying the plants of upper and lower Egypt around the emblem of union. He was worshipped at Nilopolis, and also at the shrines which marked the one hundred boating stages all along the river. Festivals were held at the rising of the Nile. Hymns in honor of the river attribute all prosperity and good to its benefits.

Ptah, the creator, was especially worshipped at Memphis. He is figured as a mummy; and we know that full length burial and mummifying begin with the dynastic period. He was identified with the earlier animal-worship of the bull Apis, but it is not likely that this originated his creative aspect, as he creates by moulding clay, or by word and will, and not by natural means. He became united with the old Memphite god of the dead, Seker, and with Osiris, as Ptah-Seker-Osiris.

Min was the male principle. He was worshipped mainly at Ekhmim and Koptos, and was there identified with Pan by the Greeks. He also was a god of the eastern desert. The oldest statues of gods are three gigantic limestone figures of Min found at Koptos. These bear relief designs of Red Sea shells and swordfish. It seems that he was introduced by a people coming across from the east. His worship continued till Roman times.

Hathor was the female principle whose animal was the cow. She is identified with the mother Isis. She was also identified with other earlier deities and her forms are very numerous in different localities. There were also seven Hathors who appear as fates, presiding over birth.