AscendingPassage.com

See a list of chapters.

Abydos

most ancient of cities

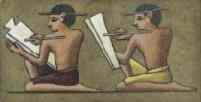

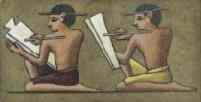

Nomes bring offerings to Ramses II at Abydos.

Photograph by Olaf Tausch, CreativeCommons.

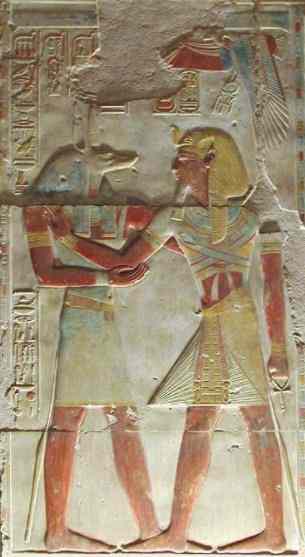

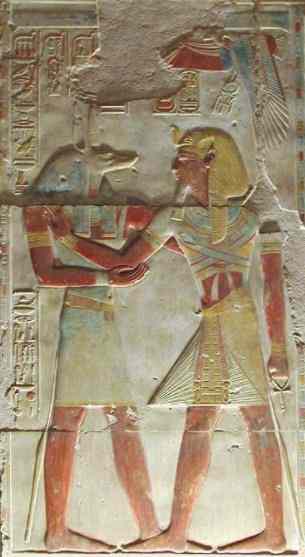

Abydos is some distance from the Nile, which may explain why David Roberts and other artists missed it. A shame, because the artwork of the great Temple of Seti I (Sety) is among Egypt's best. The photo below of Pharaoh Seti gives an idea of the rich detail of these low relief sculptures, carved over 3000 years ago. Seti Photo by Messuy, 2005 License

Seti's Temple at Abydos

Edited excerpt from La Mort De Philae

Edited excerpt from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti, 1909, 1924

-- A CHARMING LUNCHEON --

... of temples and tourists in Abydos

We are making our way through the fields of Abydos (Abtu) in the dazzling

splendor of the forenoon. We have come, like so many pilgrims of old, to visit the sanctuaries of Osiris. It is a journey of some ten miles or so, under a clear sky and a

burning sun.

Abydos! What magic there is in the name! "Abydos is at hand, and with

a short horse ride we shall be there." The mere words seem somehow to

transform the aspect of the homely green fields, and make this

pastoral region almost imposing. The buzzing of the flies increases in

the overheated air and the song of the birds subsides until at last it

dies away in the approach of noon.

We have been journeying a little more than an hour when

suddenly, beyond the little houses and trees of a village, quite a

different world is disclosed--the familiar yet always strange desert. The town of Abydos, which has vanished and left nothing behind, rose

once in this spot, on the very threshold of the

desert. The temples and tombs of Abydos, more venerated even than those of

Memphis, are a little farther on.

This domain of light and drought is shaded and streaked with brown, red and

yellow colors. The horizon trembles under the little

vapors of mirage like water ruffled by the wind. The background mounts gradually to the foot of the Libyan mountains. The whole region is strewn

with debris of bricks and stones, shapeless ruins which, though

they scarcely rise above the sand, abound in great

numbers. They serve to remind us that here indeed is a very ancient

soil, where men labored in centuries that have drifted out of

knowledge. One divines instinctively the catacombs, the

tombs and the mummies that lie below!

These graveyards of Abydos exercised for thousands of years

an extraordinary fascination over this people who dwelt in the valley of the Nile. According to truly ancient tradition, the head of Osiris, the lord of the

other world, reposes in the depths of one of the temples which

today are buried in the sands. Men, from primeval night, held the idea

that there were localities helpful to the souls

that lay beneath the earth. Certain holy places behove them to be buried if they wished to be ready when the

signal of awakening was given.

In old Egypt each one,

at the hour of death, turned his thoughts to these stones and sands of Abydos,

in the ardent hope that he might be able to sleep near the remains of

his god. And when the place became crowded with sleepers, those

who could obtain no place there conceived the idea of having humble

stone stelae planted on the holy ground. Some arranged that their mummies might be there for some

weeks, even if they were afterwards removed. And thus, funeral

processions passed to and fro without ceasing through the fields

that separate the Nile from the desert.

Seti's Temple at Abydos

Engraving by Samuel Manning, 1875.

The first great temple--that which King Seti I raised to the mysterious

Osiris--is

quite close. We come upon it suddenly, so that it almost startles us,

for nothing warns us of its proximity. The

marvellously conserving sand had buried it under its tireless

waves and preserved it almost intact untill the present day. The temple has been

exhumed, but the sand still rises almost to its

roof.

Through an iron gate, guarded by two tall Bedouins in

black robes, we plunge at once into the shadow of enormous stones. We

are in the house of the god, in a forest of heavy columns. We are

surrounded by a world of people carved in bas-

relief on the pillars and walls--people who seem to be signalling one

to another and exchanging among themselves mysterious signs.

Through an iron gate, guarded by two tall Bedouins in

black robes, we plunge at once into the shadow of enormous stones. We

are in the house of the god, in a forest of heavy columns. We are

surrounded by a world of people carved in bas-

relief on the pillars and walls--people who seem to be signalling one

to another and exchanging among themselves mysterious signs.

But what is this noise in the sanctuary? It seems to be full of

people. There, sure enough, beyond a second row of columns, is quite a

crowd talking loudly. I fancy that I can hear the

clinking of glasses and the tapping of knives and forks. Oh! poor, poor temple, to what strange uses have you come. . . . Behold a table set for some thirty guests,

and the guests themselves, drinking whisky and soda, and eating voraciously sandwiches out of greasy paper, which now litters the floor.

They belong to that special type of humanity which patronizes Thomas Cook &

Son (Egypt Ltd.).

This kind of thing, so

the black-robed Bedouin guards inform us, is repeated every day so

long as the season lasts. A luncheon in the temple of Osiris is part

of the program of pleasure trips. Each day at noon a new band

arrives, on bored and unfortunate donkeys. The tables and the

crockery remain, of course, in the old temple!

Let us escape quickly, if possible before the sight shall have become

graven on our memory.

The Temple of Ramesses II at Abydos

Temple of Ramsses II,

from an old postcard.

Without conviction now, we make our way towards another temple,

guaranteed solitary. Indeed the sun blazes there a lonely sovereign in

the midst of a profound silence, and Egypt and the past take us again

into their folds.

This sanctuary was built by Ramses II, son of Seti I, and also dedicated to Osiris. The sands

covered it with their winding sheet, but were able to

preserve for us only the lower and more deeply buried parts. Not long ago a manufacturer, discovering that the limestone of its walls was friable, used this temple as a quarry, and for some years bas-reliefs beyond price served the mills of the factory. The ruins,

protected and cleared as they are today, rise only some ten or twelve

feet from the ground. The majority of the figures in the bas-reliefs

have only legs and a portion of the body; their heads and shoulders

have disappeared with the upper parts of the walls.

The goddess Heqet, Temple of Ramesses II,

Photograph by Olaf Tausch, CreativeCommons.

But they seem to

have preserved their vitality: the gesticulations, the exaggerated

pantomime of the attitudes of these headless things are more striking than if their faces still remained. And they

have preserved too, in an extraordinary degree, the brightness of

their antique paint, the fresh tints of their costumes, of their

robes of turquoise blue, or lapis, or emerald-green, or golden-yellow.

It amazes us by

remaining perfect after thirty-five centuries.

All that these people

did seems as if made for immortality. Such

brilliant colors are not found in many of the other Pharaonic

monuments, and here they are heightened by the white background.

For, excepting the bluish, black and red granite of the

porticoes, the walls are all of a fine limestone, of exceeding

whiteness. The holy of holies is built of a pure alabaster.

Above the truncated walls, with their bright clear colors, the desert

appears, quite brown by contrast. One sees the great yellow

swell of sand and stones above the pictures of these decapitated

people. It rises like a colossal wave and stretches out to bathe the

foot of the Libyan mountains beyond. Towards the north and west, shapeless ruins of tawny-colored blocks follow one another

in the sands until the dazzling distance ends in a clear-cut line

against the sky. Apart from this temple of Ramses, where we now stand,

and that of Seti in the vicinity, where the enterprise of Thomas Cook

& Son flourishes, there is nothing around us but ruins, crumbled and

pulverised beyond all possible redemption. They give us pause,

these disappearing ruins, for somewhere among them is the debris of that ageless

temple where sleeps the head of the god. Abydos, so old that it

almost makes one giddy to think of the beginning.

Here, as at Thebes and Memphis, the tombs of the Egyptians are only among the sands and the parched rocks. The great ancestral

people liked to place its embalmed dead in the

midst of this luminous, changeless, nearly lifeless splendour, which men call

the desert.

Pharaoh Seti with five goddesses.

Photograph from the Temple of Seti at Abydos.

And what is this now that is happening in the holy neighborhood of

unhappy Osiris? A troupe of donkeys, belaboured by Bedouin drivers, is

being driven in the direction of the adjacent Seti temple! The luncheon no doubt is over and the band about to

depart, sharp to the appointed hour of the program. They all mount into their saddles, these Cooks and

Cookesses, and opening their

white cotton parasols, take themselves off in the direction of the

Nile. They disappear and the place belongs to us.

When we venture at last to return to the first sanctuary the guardians are busy clearing

away the dirty paper and the dubious

crockery. All this happily ends with the first hypostyle. Nothing dishonours the

halls of the interior, where silence has again descended, the vast

silence of noon in the desert.

Photo by Zangaki 1860

In the reign of the Emperor Tiberius, men already marvelled at this

temple, as a relic of the most distant and nebulous past. The

geographer Strabo wrote in those days: "It is an admirable palace

built in the fashion of the Labyrinth save that it has fewer

galleries."

There are galleries enough however, and one can readily

lose oneself in its mazy turnings. Seti built seven chapels, consecrated to

Osiris and to different gods and goddesses, seven vaulted

chambers, seven doors for the processions of the gods,

and, at the sides, numberless halls, corridors, secondary chapels,

dark chambers and hidden doorways.

Gigantic columns,

suggestive of reeds and resembling a stem of papyrus, rise here in a

thick forest to support the stones of the blue ceilings, which are

strewn with stars.

In many

cases stones are missing and leave large openings to the real

sky above. The sun of

so many centuries cracked them, and their own weight brought them headlong to the ground. Floods of light now enter

through the gaps, into the very chapels where the men of old had

thought to ensure a holy gloom.

Seti I offers incense to Horus and Osiris, Abydos Temple

photo by Zangaki, c.1880.

Despite the damage which has overtaken the ceilings, this is

nevertheless one of the most perfect of the sanctuaries of ancient

Egypt. The sands, those gentle sextons, have here succeeded

miraculously in their work of preservation. They might have been

carved yesterday, these innumerable people.

The whole temple, with the openings which give it light, is more

beautiful perhaps than in the time of the Pharaohs. In place of the

old-time darkness, a transparent gloom now alternates with shafts of

sunlight. Here and there the subjects of the bas-reliefs, so long

buried in the darkness, are deluged with burning rays. The sunlight shows in detail

their attitudes, their muscles, their scarcely altered colors, and

endows them again with life and youth.

There is no part of the wall, in

this immense place, that is not covered with divinities, with hieroglyphs

and emblems. Osiris, jackal-headed Anubis, falcon-headed Horus, and ibis-headed

Thoth are repeated a thousand times, welcoming with strange gestures

the kings and priests who are rendering them homage.

The bodies, almost nude, with broad shoulders and slim waist, have a

slenderness, a grace, and the features of the faces

are of an exquisite purity. The artists who carved these charming

heads, with their long eyes, full of the ancient dream, were already

skilled in their art. They used a convention which puzzles us today, they

only drew faces in profile. All the legs, all the feet are

in profile too, although the bodies confront us fully. Symbolism and magic were the intent of their art, a larger size showed greater importance, there was no need for perspective.

Seti with (L)Anubis and (R)Isis

Photographs from EgyptArchive

Many of the pictures represent King Seti, drawn without doubt from

life, for they show us almost the very features of his mummy. At his side he holds

affectionately his son, the prince-royal, Ramses (later on Ramesses II.,

known to the Greeks as the great Sesostris). They have given the latter quite a

frank air, and he wears a curl on the side of his head, as was the

fashion in childhood.

Seti and his son Ramesses catch a bull.

Photograph from EgyptArchive.

We thought we had finished with the Cooks and Cookesses of the

luncheon, but alas! Our horses, faster than their donkeys, overtake

them on the return journey among the green fields. At a stoppage in the narrow roadway, caused by a meeting with a number

of camels laden with lucerne, we are brought to a halt in their midst.

Almost touching me is a dear little white donkey, who looks at me

pensively and in such a way that we at once understand each other. A

mutual sympathy unites us. A Cookess in blue spectacles surmounts him, bony and severe. Over her traveling

costume she wears a tennis jersey,

which accentuates the angularity of her figure. In her person she

seems the very incarnation of the respectability of the British Isles.

So long are those legs of hers--it would be more equitable if she were carrying the donkey.

Almost touching me is a dear little white donkey, who looks at me

pensively and in such a way that we at once understand each other. A

mutual sympathy unites us. A Cookess in blue spectacles surmounts him, bony and severe. Over her traveling

costume she wears a tennis jersey,

which accentuates the angularity of her figure. In her person she

seems the very incarnation of the respectability of the British Isles.

So long are those legs of hers--it would be more equitable if she were carrying the donkey.

The poor little white donkey regards me with melancholy. His ears

twitch restlessly and his big beautiful eyes, so fine, so observant of

everything, say to me as plain as words:

"She is a beauty, isn't she?"

"She is, indeed, my poor little donkey. But think of this: fixed on

your back as she is, you have this advantage over me--you see her

not!"

But my reflection, though judicious enough, does not console him, and

his look answers me that he would be much prouder if he carried, like

so many of his comrades, a simple pack of sugarcane.

Edited and excerpted from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti (France), 1909, 1924

Go to the NEXT CHAPTER.

Unknown to M. Loti, a strange underground chamber lay behind Seti's Temple.

Professor Petre and Ms Murray's report of the discovery: Osirion at Abydos

There is a lot more to Abydos, Mr Petre's description: Monuments of Abydos

Ra-Horakhty, Seti I and Horus.

Photograph from EgyptArchive.

The Plan of Seti I's Temple at Abydos

from the Mariette expedition, 1869.

The support areas were to the left, unlike all other temples

where they are directly behind the sanctuary.

This allows the Osirion to occupy that space

as a more important position than the sanctuary.

Countless beautiful 19th century images of ancient Egypt

and 75 pages of architecture, art and mystery

are linked from the library page:

The Egyptian Secrets Library

Edited excerpt from La Mort De Philae

Edited excerpt from La Mort De Philae

Through an iron gate, guarded by two tall Bedouins in

black robes, we plunge at once into the shadow of enormous stones. We

are in the house of the god, in a forest of heavy columns. We are

surrounded by a world of people carved in bas-

relief on the pillars and walls--people who seem to be signalling one

to another and exchanging among themselves mysterious signs.

Through an iron gate, guarded by two tall Bedouins in

black robes, we plunge at once into the shadow of enormous stones. We

are in the house of the god, in a forest of heavy columns. We are

surrounded by a world of people carved in bas-

relief on the pillars and walls--people who seem to be signalling one

to another and exchanging among themselves mysterious signs.

Almost touching me is a dear little white donkey, who looks at me

pensively and in such a way that we at once understand each other. A

mutual sympathy unites us. A Cookess in blue spectacles surmounts him, bony and severe. Over her traveling

costume she wears a tennis jersey,

which accentuates the angularity of her figure. In her person she

seems the very incarnation of the respectability of the British Isles.

So long are those legs of hers--it would be more equitable if she were carrying the donkey.

Almost touching me is a dear little white donkey, who looks at me

pensively and in such a way that we at once understand each other. A

mutual sympathy unites us. A Cookess in blue spectacles surmounts him, bony and severe. Over her traveling

costume she wears a tennis jersey,

which accentuates the angularity of her figure. In her person she

seems the very incarnation of the respectability of the British Isles.

So long are those legs of hers--it would be more equitable if she were carrying the donkey.