AscendingPassage.com

See a list of chapters.

The Crypt of

Pharaoh Amenophis

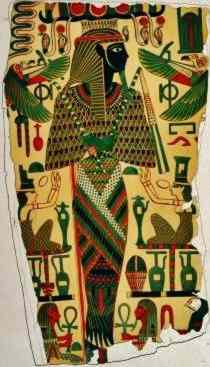

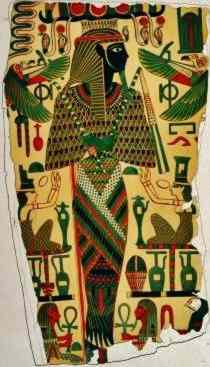

Anubis prepares the mummy,

from the papyrus of Ani,

by Salvador Cherubini.

Excerpted from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti, 1924

Deep in the tomb of Pharaoh Amenophis...

The soul used to depart simultaneously under two forms: a

flame [The Khou, which never returned to our world] and a falcon [The Bai (Ba), which might, at its will, revisit the tomb]. And this country of shadows,

called also the West, to which the soul had to journey, was where

the moon sinks and where each evening the Sun goes down. It is a country to

which the living were never able to attain, it fled before

them, however fast they might travel across the sands.

On its arrival there, the soul had to parley

successively with the fearsome demons who lay in wait for it along its

route. If at last it was judged worthy to approach Osiris, the soul was subsumed in him and reappeared as a star, shining over the

world the next morning and on all succeeding mornings until the

consummation of time. It was a vague survival in solar splendour, a

continuation without personality, parallel to Buddhist no-thingness.

To care for the Bai it was thought necessary to preserve the body at whatever cost,

for the Bai of the dead man continued to dwell in the dry

flesh, and retained a kind of partial life, barely conscious. Sometimes, too, this double, escaping

from the mummy and its box, would wander like a phantom about the

tomb. In order that at such times it might be able to obtain

nourishment, a mass of mummified viands were

among the thousand and one things buried at its side. Even natron

and oils were left, so that it might re-embalm itself.

And for Amenophis II this more or less is the story of his

Bai:

After three or four

hundred years passed, lulled in heavy slumber, he heard the sound of muffled blows

in the distance, by the side of the hidden well. The secret entrance

was discovered: men were breaking through its walls! Living beings

were about to appear, pillagers of tombs, no doubt, come to rob, to destroy!

But no! It is the chanting priests of Osiris, advancing, trembling, in

a funeral procession. With them they brought nine great coffins, the

mummies of nine kings. Amenophis was joined by his sons, grandsons and other unknown

successors, down to King Setnakht, who governed Egypt two and a

half centuries after him. It was to hide them better that they

brought them hither, and placed them all together in a chamber that

was immediately walled up. Then they departed. The stones of the door

were sealed afresh, and everything fell again into the old mournful

and burning darkness.

Slowly the centuries rolled on--perhaps ten, perhaps twenty--in a

silence no longer even disturbed by the scratchings of the insects. And a day came when the same

blows were heard again at the entrance . . . . This time it was the robbers.

Carrying torches in their hands, they rushed headlong in, with shouts

and cries. Everything was plundered except the hiding-place of the nine coffins. Then, when they had secured

their booty, they walled up the entrance as before. They left an inextricable confusion of shrouds, of shattered vases, of broken gods and emblems.

by Prisse d'Avennes 1878

Afterwards, for long centuries, there was silence again. Finally,

in our days, the Bai perceived the noise of stones being unsealed by blows

of pickaxes yet again. The third time, the living men who entered were of a kind

never seen before. At first they seemed respectful and pious, only

touching things gently.

But they came to plunder everything, even the

nine coffins in their still inviolate hiding-place. They gathered the

smallest fragments with a solicitude almost religious. That they might

lose nothing they sifted the rubbish and the dust. But, as for

Amenophis, who was already nothing more than a lamentable mummy,

without jewels or bandages, they left him at the bottom of his

sarcophagus of sandstone. And since that day, doomed to receive each

morning numerous people of a strange aspect, he dwells alone in his

tomb, where there is now neither a being nor a thing belonging to

his time.

And then, suddenly, black night! And we stand as if congealed in our

place. The electric light has gone out--everywhere at once. Above, on

the Earth, midday must have sounded for those who still have

awareness of the Sun and the hours.

And then, suddenly, black night! And we stand as if congealed in our

place. The electric light has gone out--everywhere at once. Above, on

the Earth, midday must have sounded for those who still have

awareness of the Sun and the hours.

The guard who has brought us hither shouts in his Bedouin falsetto to get the light switched on again, but the infinite thickness

of the walls, instead of prolonging the vibrations, seems to deaden

them. Who could hear us, in the depths where we now are?

Then, groping in the absolute darkness, he makes his way up the

sloping passage. The hurried patter of his sandals and the flapping of

his burnous grow faint in the distance, and the cries that he

continues to utter soften and fade, so smothered that it seems we might

ourselves be buried. Meanwhile we do not move.

But how comes it

that it is so hot among these mummies? It seems as if there were

fires burning in some oven close by. And above all there is a want of

air. Perhaps the corridors, after our passage, have contracted, as

happens sometimes in the anguish of dreams. Perhaps the long fissure

by which we have crawled hither has closed in upon us.

The Weighing of the Heart.

by G. Angelelli ,1832

At length the light is turned on

again. The Bedouin is now returned, breathless from his journey. He urges us

to come to see the king before the electric light is again

extinguished, and this time permanently.

Tomb of Rameses VI.

Hand colored photo from Elysian Fields c.1920.

Star Chart, roof of the crypt, tomb of Ramesses VII

The sky goddess Nut reaches over two lines of constellations.

From La Description de l'Egypte, 1809.

Behold us now at the end

of the hall, on the edge of a dark crypt, leaning over and peering

within. It is a place oval in form, with a vault of black,

relieved by frescoes, either white or the color of ashes. They

represent, these frescoes, a whole new register of gods and demons,

some slim and sheathed narrowly like mummies, others with big heads

and big bellies like hippopotami. Placed on the ground and watched

from above by all these figures is an enormous sarcophagus of stone,

wide open. In it we can distinguish vaguely the outline of a human

body: the Pharaoh!

Behold us now at the end

of the hall, on the edge of a dark crypt, leaning over and peering

within. It is a place oval in form, with a vault of black,

relieved by frescoes, either white or the color of ashes. They

represent, these frescoes, a whole new register of gods and demons,

some slim and sheathed narrowly like mummies, others with big heads

and big bellies like hippopotami. Placed on the ground and watched

from above by all these figures is an enormous sarcophagus of stone,

wide open. In it we can distinguish vaguely the outline of a human

body: the Pharaoh!

We should have liked to see him better. The necessary light

is forthcoming at once: the Bedouin touches

an electric button and a powerful lamp illuminates the face of

Amenophis, detailing with a clearness that almost frightens you: the

closed eyes, the grimacing countenance, and the whole of the sad

mummy. This theatrical effect took us by surprise; we were not

prepared for it.

He was buried in magnificence, but the pillagers have stripped him of

everything, even of his beautiful breastplate of tortoise shell, which

came to him, a gift from a far-off Oriental country. For many centuries

now he has slept half naked on his rags. But his poor bouquet is there

still--of mimosa, recognisable even now. Who will ever tell what

pious or perhaps amorous hand it was that gathered these flowers for

him more than three thousand years ago?

The heat is suffocating. The whole crushing mass of this mountain into which we have crawled like white ants seems to weigh upon

our chest. And these figures too, inscribed on every side, and this

mystery of the hieroglyphs and the symbols, cause a growing

uneasiness. You are too near them, they seem too much the masters of

the exits, these gods with their heads of falcon, ibis and jackal.

On the walls they converse in a continual exalted pantomime.

From the tomb of Ramsses IX.

And then

the feeling comes over you, that it is sacrilege standing

there, before this open coffin, in this unwonted insolent light. The

shrunken face seems to ask for mercy:

"Yes, yes, my sepulchre has been violated and I am returning to dust.

But now that you have seen me, leave me, turn out that light, have

pity on my nothingness."

Indeed, what a mockery! To have adopted

so many stratagems to hide his corpse; to have exhausted thousands of

men in the hewing of this underground labyrinth, and to end thus, with

his head in the glare of an electric lamp, to amuse whoever passes.

I think it was the poor bouquet of mimosa that

awakened me. I say to the Bedouin: "Yes, put out the light, put it

out--that is enough."

And then the darkness returns above the royal countenance, which is

suddenly invisible in the sarcophagus. The phantom of the Pharaoh is

vanished, plunged into the unfathomable past. The audience is

at an end.

And we, who are able to escape,

ascend rapidly towards the sunshine of the living, we go to breathe

the air again, the air to which we have still a right--for some few

days longer.

Excerpted from La Mort De Philae

by Pierre Loti, 1909, 1924

NEXT CHAPTER

Anubis, Guardian of the fields of the dead.

This life-size statue was found at the foot of Tutankhamen's coffin.

Ramsses III, Exalted, from the Champollion expedition, 1835.

The Valley Of The Kings

Eternal Palaces of New Kingdom Pharaohs

The Valley of the Kings Part 1

Pharaoh Amenophis' tomb Part 2

Part 3: The Crypt

Giovanni Belzoni and the tomb of Seti I

Ancient Egyptian Artist techniques in the Tomb of Seti I

Valley of the Kings Photos

Valley of the Queens -

Queens' portraits

Valley of the Queens

Nefertari a rarely seen Egyptian treasure

Deir el Medina: Tombs of the craftsmen.

Countless beautiful 19th century images of ancient Egypt

and 75 pages of architecture, art and mystery

are linked from the library page:

The Egyptian Secrets Library

And then, suddenly, black night! And we stand as if congealed in our

place. The electric light has gone out--everywhere at once. Above, on

the Earth, midday must have sounded for those who still have

awareness of the Sun and the hours.

And then, suddenly, black night! And we stand as if congealed in our

place. The electric light has gone out--everywhere at once. Above, on

the Earth, midday must have sounded for those who still have

awareness of the Sun and the hours.

Behold us now at the end

of the hall, on the edge of a dark crypt, leaning over and peering

within. It is a place oval in form, with a vault of black,

relieved by frescoes, either white or the color of ashes. They

represent, these frescoes, a whole new register of gods and demons,

some slim and sheathed narrowly like mummies, others with big heads

and big bellies like hippopotami. Placed on the ground and watched

from above by all these figures is an enormous sarcophagus of stone,

wide open. In it we can distinguish vaguely the outline of a human

body: the Pharaoh!

Behold us now at the end

of the hall, on the edge of a dark crypt, leaning over and peering

within. It is a place oval in form, with a vault of black,

relieved by frescoes, either white or the color of ashes. They

represent, these frescoes, a whole new register of gods and demons,

some slim and sheathed narrowly like mummies, others with big heads

and big bellies like hippopotami. Placed on the ground and watched

from above by all these figures is an enormous sarcophagus of stone,

wide open. In it we can distinguish vaguely the outline of a human

body: the Pharaoh!