Ascending Passage.com

See the: Egyptian Secrets Library.

The Colossi of Memnon

by David Roberts, 1838

Guardians of the approach to the Valley of the Kings, the great statues of Pharaoh Amenhotep III were all that was known of his 18th Dynasty temple. For thousands of years these giant 50 foot (15 meter) statues stood alone in the sugar cane fields, silent and powerful. Generations of farmers calmly plowed around them, paying little heed to their import - except when the tourists crushed the crop as they crowded to see the statues up close.

Each statue originally was a single block of quartzite sandstone, weighing over 700 tons (650,000 Kg). The stone was quarried at el-Gabal el-Ahmar near Cairo and brought, somehow, 420 miles (675 km) upriver to Thebes. Fragments of four similar statues have recently been found nearby.

The two statues were ancient to the Romans, and considered to be an oracle of great power. A high whistling sound sometimes came from the north statue. Hearing it was a particularly good sign, and may explain why the statues remained standing.

The Romans added the flat base to both statues, which undoubtedly helped preserve them from groundwater. Then they replaced the top portion of the north statue, which had broken, with several layers of inferior stone. This repair ended the statue's song. It is unknown what happened to the original upper portion of the statue. Perhaps it will be found someday, buried in the garden of an ancient villa in Rome.

Recently, as a result of renewed attention to the area, a parking lot has been built nearby and the statues have been fenced. More importantly the area between the statues has been fenced, preventing the visitor from entering the temple, and indeed the entire Thebes Necropolis, at the intended place.

by Vivant Denon, 1807

In 1996 the site received a grant from the World Monuments Fund. The main concern was to protect what remained below ground from the high water table, the result of irrigation and the Aswan Dam. Previously archaeologists, and the local people, believed that all of Amenhotep III's temple except the two colossal statues and a few scattered stones had been carried off in ancient times. Fortunately quite a lot was under the soil.

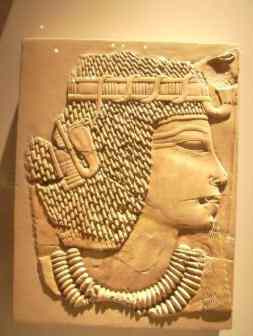

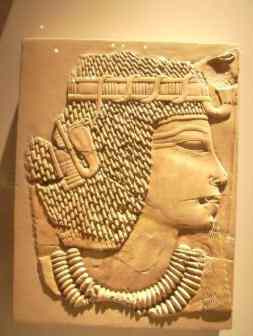

The Valley Temple of Amenhotep III (also known as his mortuary temple) is emerging from the mud as one of the largest in Egypt. Amenhotep III and his principal wife, Queen Tye (right), were builders and patrons of the arts, which reached great heights during their rule.

Amenhotep III's temple is about 2000 feet (600 meters) long and nearly as wide, making it one of the most ambitious ever built. The statues found so far include 72 fine granite images of Sekhmet the lion headed protector, and of course Pharaoh and Queen Tye. In the next twenty years, or so, it is hoped that the 3400 year old Valley Temple of Amenhotep III will be fully excavated, to be yet another reminder of what once was, on the road to the Valley of the Kings.

The Great Colossi of Memnon

by Ernst Weidenbach 1850.

(Left and Right) Amenhotep III, the pharaoh of Memnon.

Berlin Museum, photographs by Marcus Cyron, CreativeCommons.

The Colossi of Memnon

from: The Spell of Egypt

by Robert Hichens, 1911

Etext prepared by Dagny

and John Bickers

Adapted for AscendingPassage.com, 2006.

-- The Colossi of Memnon --

The peace of the plain of Thebes in the early morning is very rare and

very exquisite. It is not the peace of the desert, but rather,

perhaps, the peace of the prairie. It is an atmosphere tender, delicately

thrilling, softly bright, hopeful in its gleaming calm. Often and

often have I left the boat Loulia very early moored against the long sand

islet that faces Luxor when the Nile has not subsided. I have rowed

across the quiet water that divided me from the western bank, and,

with a happy heart, I have entered into the lovely peace of the great

spaces that stretch from the Colossi of Memnon to the Nile, to the

mountains.

Think of the timbre of the reed flute's voice,

thin, clear, and frail as dewdrops. Think of the

torrents of spring rushing through the veins of a great, wide land growing almost still at last on their journey. Spring, you will

say, perhaps, and high Nile not yet subsided! But Egypt is the favored

land of a spring that is already alert at the end of November, and in

December is pushing forth its green. The Nile has sunk away from the

feet of the Colossi that it has bathed through many days. It has freed

the plain to the fellaheen, though still it keeps my island in its

clasp. And the god of the Nile, Hapi, or Kam-wra, the "Great Extender," and the Sun, Ra, have made

this wonderful spring to bloom on the dark earth before Christmas.

Think of the timbre of the reed flute's voice,

thin, clear, and frail as dewdrops. Think of the

torrents of spring rushing through the veins of a great, wide land growing almost still at last on their journey. Spring, you will

say, perhaps, and high Nile not yet subsided! But Egypt is the favored

land of a spring that is already alert at the end of November, and in

December is pushing forth its green. The Nile has sunk away from the

feet of the Colossi that it has bathed through many days. It has freed

the plain to the fellaheen, though still it keeps my island in its

clasp. And the god of the Nile, Hapi, or Kam-wra, the "Great Extender," and the Sun, Ra, have made

this wonderful spring to bloom on the dark earth before Christmas.

What a pastoral it is, this plain of Thebes, in the dawn of day! Think

of the reed flute, I have said, not because you will hear it, as you

ride toward the mountains, but because its voice would be utterly in

place here, in this arcady of Egypt. One almost hears it, playing no tarantella, but one of

those songs, half bird-like, and half sadly, mysteriously human, which

come from the soul of the East. You may catch distant

cries from the bank of the river where the shadoof-man toils, lifting

ever the water. His voice, and the creaking lay of the water-wheel, pervade Upper

Egypt like an atmosphere. Perhaps at first it

irritates, at last it seems to you the sound of the soul of the river, of

the sunshine, and the soil.

Much of the land looks painted. So flat is it, so young are the

growing crops, that they are like a coating of green paint spread over

a mighty canvas. But the grain rises higher than the heads of the children who stand among it to watch you canter past. And in the

far distance you see dim groups of trees--sycamores and acacias,

tamarisks and palms. They mark the furthest extent of the Nile flood, the edge of the fierce desert. Beyond them is the very heart of this "land of

sand and ruins and gold": Medinet-Abu, the Ramesseum, Deir-el Medina,

Kurna, Deir-el-Bahari, the tombs of the kings, the tombs of the queens

and of the princes. In the strip of bare land at the foot of those

hard, yet poetic mountains have been dug up treasures the fame of

which has gone to the ends of the world.

But this plain, where oxen are working with ploughs that look like relics of far-

off days, is the possession of the two great presiding beings whom you

see from an enormous distance, the Colossi of Memnon. Amenhotep III (Amunophis), put them where they are in 1350 BC. So we are told. But in this early morning it

is not possible to think of them as being brought to any place.

by David Roberts, 1838

Seated, the one beside the other, facing the Nile and the

rising sun, their immense aspect of patience suggests will, calmly,

steadily exercised. It suggests choice. For some reason they chose to come to this plain. They choose solemnly

to remain there, waiting, while the harvests grow and are gathered

about their feet. They wait while the Nile rises and subsides, while the years

and the generations come, like the harvests, and are stored away in

the granaries of the past. Their calm broods over this plain, gives to

it a personal atmosphere which sets it quite apart from every other space of the world.

There is no place that I know on the earth

which has the peculiar, bright, ineffable calm of the plain of these

Colossi.

That legend of the singing at dawn, (one colossus would greet the dawn with a high, piercing wail), how

could it have arisen? How could such calmness sing, such patience ever

find a voice? Unlike the Sphinx, which becomes ever more impressive as

you draw near to it, and is most impressive when you sit almost at its

feet, the Colossi lose in personality as you approach them and can see

how they have been eroded.

Memnon by Jean Gerome, 1856

From afar one feels their minds, their strange, unearthly temperaments

commanding this pastoral. When you are beside them, this feeling

disappears. Their features are gone, and though in their attitudes

there is power, and there is something that awakens awe, they are more

wonderful as a far-off feature of the plain. They gain in grandeur

from the night, in strangeness from the moonrise, perhaps the most

when the Nile comes to their feet.

More than three thousand years old,

they look less eternal than the Sphinx. Like them, the Sphinx is

waiting, but with a greater purpose. The Sphinx reduces man really to

nothingness. The Colossi leave him some remnants of individuality. Once Strabo and AElius Gallus, Hadrian and Sabina, great men of ancient days, came over the sunlit land to hear the unearthly song in the

dawn. It seems they retained some--not much, but still some--importance here.

Before the Sphinx no one is important.

by David Roberts, 1838

But in the distance of the

plain the Colossi shed a real magic of calm and solemn personality. They subtly mingle their spirit with the flat, green world, with the soft airs that

are surely scented with an eternal springtime, and with the light that

the morning rains down as strong men work in the fields. From the patience of the

Colossi men have for centuries drawn a patience in labor that has in it

something not less sublime.

The Colossi of Memnon

excerpt from: The Spell of Egypt

by Robert Hichens, published 1911

NEXT CHAPTER

Amenhotep III built a great temple, covering over 80 acres. Much of his temple was devoted to the lion headed goddess Sekhmet, not the ram-headed Amon of the powerful temple of Karnak, across the river. Perhaps there are early signs here of the revolution the son of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, would bring.

Additional images from EgyptArchive and by Harry Fenn.

Temples of West Thebes

In the western desert,

New Kingdom pharaohs built great temples

for the everlasting worship of themselves.

Amenhotep III - Memnon

Rameses III Medinet Habu

Rameses II Ramesseum

Seti I Kourna

Queen Hatshepsut Deir el Bahari

Temples of the Craftsmen Deir el Medina

Countless beautiful 19th century images of ancient Egypt

and 75 pages of architecture, art and mystery

are linked from the library page:

The Egyptian Secrets Library

Think of the timbre of the reed flute's voice,

thin, clear, and frail as dewdrops. Think of the

torrents of spring rushing through the veins of a great, wide land growing almost still at last on their journey. Spring, you will

say, perhaps, and high Nile not yet subsided! But Egypt is the favored

land of a spring that is already alert at the end of November, and in

December is pushing forth its green. The Nile has sunk away from the

feet of the Colossi that it has bathed through many days. It has freed

the plain to the fellaheen, though still it keeps my island in its

clasp. And the god of the Nile, Hapi, or Kam-wra, the "Great Extender," and the Sun, Ra, have made

this wonderful spring to bloom on the dark earth before Christmas.

Think of the timbre of the reed flute's voice,

thin, clear, and frail as dewdrops. Think of the

torrents of spring rushing through the veins of a great, wide land growing almost still at last on their journey. Spring, you will

say, perhaps, and high Nile not yet subsided! But Egypt is the favored

land of a spring that is already alert at the end of November, and in

December is pushing forth its green. The Nile has sunk away from the

feet of the Colossi that it has bathed through many days. It has freed

the plain to the fellaheen, though still it keeps my island in its

clasp. And the god of the Nile, Hapi, or Kam-wra, the "Great Extender," and the Sun, Ra, have made

this wonderful spring to bloom on the dark earth before Christmas.