To the peoples of antiquity Egypt appeared as the very mother of magic. In the mysterious Nile country they found a magical system much more highly developed than any within their native knowledge, and the cult of the dead, with which Egyptian religion was so strongly identified, appeared to the foreigner to savour of magical practice. If the materials of the magical papyri be omitted, the accounts which we possess of Egyptian magic are almost wholly foreign, so that it is wiser to derive our data concerning it from the original native sources if we desire to arrive at a proper understanding of Egyptian sorcery.

Most of what has been written by Egyptologists on the subject of Egyptian magic has been penned on the assumption that magic is either merely a degraded form of religion, or its foundation. This is one of the results of the archæologist entering a domain--that of anthropology--where he is usually rather at a loss.

What is the origin of magic? Considerable diversity of opinion exists regarding this subject among anthropologists, yet all writers appear to have ignored one notable factor, the element of wonder, which is the true fount and source of veritable magic.

According to the warring schools of anthropology, nearly all magic is sympathetic or mimetic in its nature. For example, when the medicine-man desires rain he climbs a tree and sprinkles water upon the parched earth beneath, in the hope that the deity responsible for the weather will do likewise. When the sailor desires wind, he imitates the whistling of the gale. This system is universal, but if our conclusions are well founded, the magical element does not reside in such practices as these.

When the native performs an act of sympathetic magic he does not regard it as magical--that is, to his way of thinking it does not contain any element of wonder at all. He regards his action as a cause which will bring about the desired effect, exactly as the scientific man of today believes that if he follows certain formula certain results will be achieved.

The true magic of wonder argues from effect to cause. It would appear as if sympathy magic were merely a description of proto-science, it uses mental processes similar to those by which scientific laws are produced and scientific acts are performed. There is a spirit of certainty about it which is not found, for example, in the magic of evocation.

It would, however, be rash to attempt to differentiate sympathetic magic entirely from what I would call the "magic of wonder" at this juncture. Indeed, our knowledge of the basic laws of magic is too slight as yet to permit of such a process. We find considerable overlapping between the systems. For example, one of the ways by which persons could transform themselves into werewolves was by means of buckling on a belt of wolfskin. Thus we see that in this instance the true wonder-magic of animal transformation is in some measure connected with the sympathetic process. The idea being that the donning of wolfskin, or even the binding around one of a strip of the animal's hide, was sufficient to bestow the nature of the wolf upon the wearer.

I believe the magic of wonder to be almost entirely spiritistic in its nature, and that it consists of evocation and similar processes. Here, of course, it may be quoted against me that certain incenses, planetary signs, and other media known to possess affinities for certain supernatural beings were brought into use at the time of their evocation. Once more I admit that the two systems overlap, but that will not convince me that they are in essence the same.

Like all magic, Egyptian magic was of prehistoric origin. The man of the Egyptian Stone Age made use of the sympathetic process. That he also was fully aware of the spiritistic side of magic is certain. Animism is the mother of spiritism.

The concept of the soul was developed at a comparatively early period in the history of man. The phenomenon of sleep puzzled him. Whither did the real man go during the hours of slumber? The Palæolithic man watched his sleeping brother, who appeared to him as practically dead, at least, to perception and the realities of life.

Something seemed to have escaped the sleeper. The real, vital, and vivifying element had temporarily departed from him. Life did not cease with sleep. In a more shadowy and unsubstantial sphere he re-enacted the scenes of his everyday existence. If the man during sleep had experiences in dreamland or in distant parts, it was only reasonable to suppose that his ego, his very self, had temporarily quitted the body. Grant so much, and you have two separate entities, body and soul.

Prehistoric logic extended its soul-theory to all animate beings, and even to things inanimate. Where, for example, did the souls of men go after death? It seemed they would take up their quarters in a tree, a rock, or any suitable natural object, and the terrified native could hear their voices crying down the wind and whispering through the leaves of the forest. They made an endless clamor for things of the mortal world which they could not obtain in their disembodied condition.

All nature was animate to early man. His hunting life had made the early Egyptian exceptionally cunning and resourceful, and it would soon occur to him that he might make use of such wandering and masterless spirits as he knew were close by. In this desire, it appears to me we have one of the origins of the magic of wonder, and certainly the origin of spiritism.

Trading upon the wish of the disembodied spirit to materialize, prehistoric man would construct a fetish either in the human shape or in that of an animal, or in any presentment that squared with his ideas of spiritual existence. He usually made it of no great dimensions, as he did not believe that the alter ego, or soul, was of any great size.

By threats or coaxings he prevailed upon the wandering spirit--whom he conceived as cold, hungry, and homeless--to enter the little image, which duly became its corporeal abode. It was carefully attended. In return it was expected, by dint of its supernatural knowledge, that the soul contained in the fetish should assist its master or assistant in every possible way.

Egyptian magic differed from most other systems in that the native magician attempted to coerce certain of the gods into action on his behalf. Instances of this elsewhere are extremely rare, and it would seem as if the deities of Egypt had evolved in many cases from mere animistic conceptions. This is true in effect of all deities, but at a certain point in their history most gods arrive at such a condition of eminence that they soar far above any possibility of being employed by the magician as mere tools for any personal purpose.

We often, however, find a broken-down, or deserted, deity coerced by the magician. A great reputation is a hard thing to lose, and it is possible that the sorcerer may find in the abandoned, and therefore idle, god a very suitable medium for this purpose. It would seem the divinities of Egypt were convinced into using their power on behalf of paltry sorcerers even in the zenith of their fame.

Of all civilizations known to us through history, that of ancient Egypt is the most marvellous, most fascinating, and most rich in occult significance, yet we have still much to discover. Such fragments that survive of the ancient religions appear at first glance confusing and even grotesque.

It is necessary to remember that there was an inner as well as an outer theology, and that the occult mysteries were accessible only to those valiant and strenuous initiates who had successfully passed through a prolonged purification and course of preparation austere and difficult enough to discourage all save the most persistent and exalted spirits.

It is only available to us to wander on the outskirts of Egyptian mythology.

It has been asked why the Egyptians, who had no belief in a material resurrection, took such infinite trouble to preserve the bodies of their dead. They looked forward to a paradise in which eternal life would be the reward of the righteous, and their creed inculcated faith in the existence of a spiritual body to be inhabited by the soul which had ended its earthly pilgrimage. Such beliefs do not explain the attention bestowed upon the lifeless corpse. The explanation must be sought in the famous Book of the Dead, representing the convictions which prevailed throughout the whole of the Egyptian civilization from pre-dynastic times.

Briefly, the answer to our question is this: there was a Ka or double, in which the heart-soul was located. This Ka, equivalent to the astral body in modern terms, was believed to be able to come into touch with material things through the preserved or mummified body. This theory accords with the axiom that each atom of physical substance has its relative equivalent on the astral plane. It will therefore be understood how, in the ancient religions, the image of a god was regarded as a medium through which his powers could be manifested. "As above, so below", every living thing possessed a divine attribute.

Words in prayer were an essential article of the Egyptian religion, and the spoken word of a priest was believed to have strong potency. It had been the words of Ra uttered by Thoth which brought the universe into being. Amulets inscribed with words were consequently thought to ensure the fulfilment of the blessing expressed, or the granting of the bliss desired.

The Book of the Dead was not only a guide to the life hereafter, where they would join their friends in the realms of eternal bliss, but gave detailed particulars of the necessary knowledge, actions, and, conduct during the earthly life to ensure a future existence in the spirit world. The belief in the existence of a future life was ever before them.

Various qualities, though primarily considered a manifestation of the Almighty, were attributed each to a special god who controlled and typified one particular virtue. When we take into consideration the vast period during which this empire flourished it is natural that the external manifestations of faith should have varied as time went on.

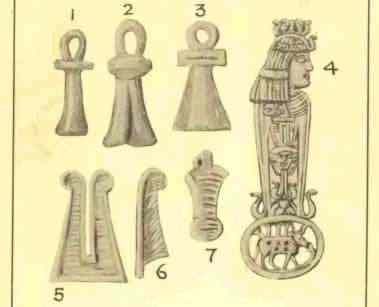

Throughout the whole of the Egyptian civilization the influence and potency of amulets and talismans was recognised in the religious services, each talisman and amulet having a specified virtue.

Certain amulets not only were worn during life, but were attached to the dead body. They are described in the following notes:

The Crux Ansata, Ankh or Ank (see Illustrations Nos. 1, 2, 3, Plate I-A), was known as the symbol of life, the loop at the top of the cross consisting of the hieroglyphic Ru (O) set in an upright form, meaning the gateway, or mouth. The creative power was signified by the loop which represents a fish's mouth giving birth to water as the life of the country. The inundations brought renewal of the fruitfulness of the earth to those who depended upon its increase to maintain life. It was regarded as the key of the Nile which overflowed periodically and so fertilized the land.

It was also shown in the hands of the Egyptian kings, at whose coronations it played an important part. The gods are invariably depicted holding this symbol of creative power. It was also worn to bring knowledge, power, and abundance.

It had reference to the spiritual life for it was from the Crux Ansata, or Ankh, that the symbol of Venus originated. The circle over the cross showed the triumph of spirit, represented by the circle, over matter, shown by the cross.

The Menat (Illustrations Nos. 4, 7, Plate I-A), were specially dedicated to Hathor, who was a form of Isis. It was worn for conjugal happiness, as it gave power and strength to the organs of reproduction, promoting health and fruitfulness. It frequently formed a part of a necklace, and was elaborately ornamented. No, 4 from the British Museum is a good specimen, the cow being an emblem of the maternal qualities which were the attributes of the goddess, who stood for all that is good and true in wife, mother, and daughter.

The Two Plumes (Illustration No. 5, Plate I-A), are sun amulets and the symbols of Ra and Thoth. The two feathers are typical of the two lives, spiritual and material. This was worn to promote uprightness in dealing, enlightenment, and morality, being symbolical of the great gods of light and air.

The Single Plume (Illustration No. 6, Plate I-A), was an emblem of Maat, the female counterpart of Thoth, who wears on her head the feather characteristic of the phonetic value of her name. She was the personification of integrity, righteousness, and truth.

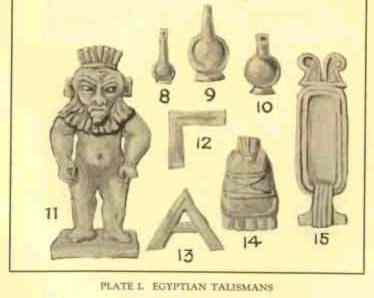

Illustrations Nos. 8, 9, 10, Plate I-B, show three forms of the Nefer, a symbol of good luck, worn to attract success, happiness, vitality, and friends.

The Cartouche, or Name Amulet (Illustration No. 15, Plate I-B : shown without a name inside), was worn to secure favor, recognition, and remembrance, and to prevent the name of its wearer being blotted out in the next world. This is a very important amulet, as the name was believed to be an integral part of the man, without which his soul could not come before God. It was most essential that the name should be preserved, in order, as described in the Book of the Dead, "thou shalt never perish, thou shalt never, never come to an end".

The amulets of the Angles (see Illustrations Nos. 12, 13, Plate I-B) and the Plummet (No. 14 on the same Plate), were symbols of the god Thoth, and were worn for moral integrity, wisdom, knowledge, order, and truth. Thoth was the personification of law and order, being the god who worked out the creation as decreed by the god Ra. He knew all the words of power and the secrets of all hearts, and may be regarded as the chief recording angel. He was also the inventor of all arts and sciences.

Bes, shown in Illustration No. 11, Plate I-B, was a very popular talisman, being the god of laughter, merry-making, and good luck. Some authorities consider him to be a foreign importation from pre-dynastic times, and he has been identified with Horus and regarded as the god who renewed youth. He was also the patron of beauty, the protector of children, and was undoubtedly the progenitor of the modern Billiken.

Illustrations Nos. 15, 19, Plate II-A, are examples of the Aper, which symbolised providence and was worn for steadfastness, stability, and alertness.

The Tat (Djed) (Illustrations Nos. 16, 17, 18, Plate II-A) held a very important place in the religious services of the Egyptians. The Djed pillar formed the center of the annual ceremony of the setting-up of the Tat, a service held to commemorate the death and resurrection of Osiris. This symbol represents the building-up of the backbone and reconstruction of the body of Osiris. In their services the Egyptians associated themselves with Osiris, through whom they hoped to rise glorified and immortal, and secure everlasting happiness. The four cross-bars symbolise the four cardinal points, and the four elements of earth, air, fire and water, and were often very elaborately ornamented (see Illustration No. 17, Plate II-A, taken from an example at the British Museum). It was worn as a talisman for stability and strength, and for protection from enemies. The Djed allows that doors--or opportunities--might be open both in this life and the next. A Tat of gold set in sycamore wood, which had been steeped in the water of Ankham flowers, was placed at the neck of the deceased on the day of interment. It would protect him on his journey through the underworld and assist him in triumphing over his foes, that he might become perfect for ever and ever.

The Heart was believed to be the seat of the soul, and Illustrations Nos. 20, 21, 22, Plate II-A, are examples of these talismans worn for protection. According to Egyptian lore, at the judgment of the dead the heart is weighed, if found perfect it is returned to its owner, who immediately recovers his powers of locomotion and becomes his own master, with strength in his limbs and everlasting felicity in his soul.

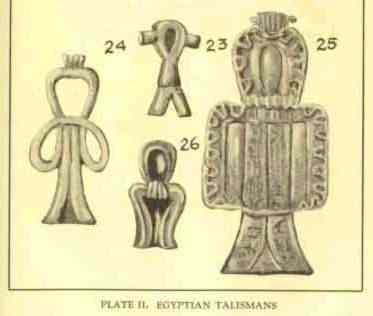

The Tie, or Sa (Illustration No. 23, Plate II-B) is the symbol of Ta-urt, the hippopotamus-headed goddess, who was associated with the god Thoth, the personification of divine intelligence and human reason. It was worn for magical protection.

The buckle of the girdle of Isis was worn to obtain the good-will and protection of this goddess, and symbolised her strength and power. Frequently made of carnelian it was believed to protect its wearer from every kind of evil and to secure the good-will of Horus. When placed like the golden Tat at the neck of the dead on the day of the funeral it opened up all hidden places in the soul's journey through the underworld and procured the favor of Isis and her son, Horus. (See Illustrations Nos. 24, 25, 26, Plate II-B.)

The Scarab was the symbol of Khepera, a form of the sun-god who transforms inert matter into action, creates life, and typifies the glorified spiritual body that man shall possess at the resurrection. From the enormous number of scarabs that have been found, this must have formed the most popular of the talismans.

The symbol was derived from a beetle, common in Egypt, which deposits its eggs in a ball of clay. The action of the insect in rolling this ball along the ground was compared with the sun itself in its progress across the sky. As the ball contained the living germ which (under the heat of the sun) hatched out into a beetle, so the scarab became the symbol of creation. It is also frequently seen holding the disk of the sun between its claws, with wings extended.

Scarabs of green stone with rims of gold were buried in the heart of the deceased, or laid upon the chest, with a written prayer for his protection on the day of judgment. Words of power were frequently recited over the scarab which was placed under the coffin as an emblem of immortality so that no one could harm the dead in his journey through the underworld. It is said the scarab was associated with burial as far back as the fourth dynasty (about 2600 B.C.). It represented matter about to pass from a state of inertness into active life. The scarab was considered a fitting emblem of resurrection and immortality, typifying not only the sun's disk, but the evolutions of the soul throughout eternity.

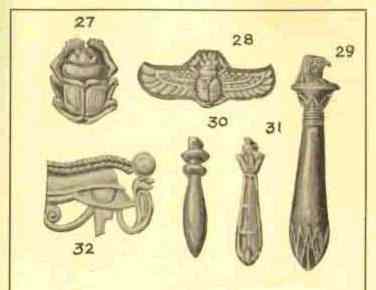

It was also worn by the Egyptian warriors in their signet rings for health, strength, and virility. It was thought that this species of beetle was all males, so that it would attract all manly qualities, both of mind and body. For this reason it was very popular as gifts between friends, many scarabs being found with good wishes or mottoes engraved on the under side, and some kings used the back of scarabs to commemorate historical events. (see Illustrations Nos. 27, 28, Plate III-A).

Next to the scarab, the ancient Egyptians attached much importance to the Eye Amulet. From the earliest astral mythology the eye was represented by a point within a circle and was associated with the pole star, which, from its fixity, was taken as a type of the eternal unchangeable. Thus it was a fitting emblem of fixity of purpose, poise, and stability. Later it was one of the hieroglyphic signs of the sun-god Ra, and represented the one supreme power casting his eye over all the world. Instead of the point within the circle it is sometimes represented as a wide open eye.

This symbol was also assigned to Osiris, Isis, Horus, and Ptah. The amulet known as the Eye of Osiris would watch over and guard the soul of the deceased during its passing through the darkness to the life beyond.

The eye was also worn by the living to ensure health and protection from the blighting influence of black magic. It would bring the stability, strength, and courage of Horus, the wisdom and understanding of Ptah, and the foresight of Isis.

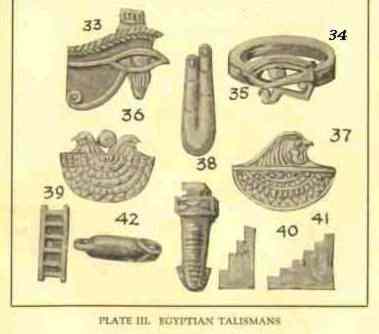

It was also extensively used in necklaces on account of the idea that representations of the eye itself would watch over and guard its wearer from the malignant glances of the envious. Examples of eye amulets are illustrated on Plate III-A, Nos. 32 and Plate III-B, Nos. 33 and 34.

When two eyes are used together the right eye is symbolic of Ra, or Osiris and the sun, while the left eye represents Isis, or the moon. The word Utchat signifying "strength" was applied to the sun when he enters the summer solstice about June 22d. His strength and power on earth was greatest at that time.

The talisman of the Two Fingers (Illustration No. 35, Plate III-B) was symbolical of help, assistance, and benediction, typified by the two fingers extended by Horus to assist his father in mounting the ladder suspended between this world and the next. This amulet was frequently placed in the interior of the mummified body to enable the departed to travel quickly to the regions of the blest. Amongst the ancient Egyptians the fingers were ever considered an emblem of strength and power, the raising of the first two fingers being regarded as a sign of peace and good faith. The first finger indicates divine will and justice, the second representing the holy spirit, the mediator, a symbolism handed down to us in the ecclesiastical benediction.

The Collar Amulet (Illustrations Nos. 36, 37, Plate III-B) was a symbol of Isis, and was worn to procure her protection and the strength of her son Horus. In both examples the head of the hawk appears, this bird being attributed to Horus as well as to Ra. This collar, which was made of gold, was engraved with words of power and seems to have been chiefly used as a funeral amulet.

The Sma (Illustration No. 38, III-B) was a favorite amulet from the dawn of Egyptian history, and is frequently used in various forms of decorated art. It was symbolic of union and stability of affection, and was worn to strengthen love and friendship and ensure physical happiness and faithfulness.

The Ladder is a symbol of Horus, and was worn to secure his assistance in overcoming and surmounting difficulties in the material world, as well as to form a connection with the heaven world, or land of light. The earliest traditions place this heaven world above the earth, its floor being the sky, and to reach this a ladder was deemed necessary.

From the pyramid texts it seems there were two stages of ascent to the upper paradise, represented by two ladders, one being the ladder of Sut, forming the ladder of ascent from the land of darkness, and the other the ladder of Horus reaching the land of light (Illustration No. 39, Plate III-B>).

The mystic ladder seen by Jacob in his vision, and the ladder of seven steps known to the initiates of Egypt, Greece, Mexico, India, and Persia will be familiar to students of occultism.

'The Steps (Illustrations Nos. 40, 41, Plate III-B) are a symbol of Osiris, who is described as the god of the staircase, through whom it was hoped the deceased might reach the heaven world and attain everlasting bliss.

The Snake's Head talisman (Illustration No. 42, Plate III-B). The serpent was generally regarded as a protecting influence. For this reason serpents were often sculptured on either side of the doorways to the tombs of kings, temples, and other sacred buildings to guard the dead from enemies of every kind.

It was also placed round the heads of divinities and round the crowns of their kings as a symbol of royal might and power. A serpent form of Tem, the son of Ptah, is thought by some authorities to have been the first living man god of the Egyptians, and the god of the setting sun. Tem was typified by a huge snake, and it is curious to note that among country folk at the present day there is a popular belief that a serpent will not die until the sun goes down.

The Sun's Disk talismans (Illustrations No. 43, 45, Plate IV-A) are symbols of the god Ra, No. 45 being appropriately placed upon the head of a ram, the symbol of the zodiacal house Aries, in which sign the sun is exalted. It was worn for power and renown, and to obtain the favors of the great ones, being also an emblem of new birth and resurrection.

The Frog talisman (Illustration No. 44, Plate IV-A) was highly esteemed, and is an attribute of Isis, being worn to attract her favors and for fruitfulness. Because of its fertility its hieroglyphic meaning was an immense number. It was also used as a symbol of Ptah, as it represented life in embryo. By the growth of its feet after birth it typified strength from weakness, and was worn for recovery from disease, also for health and long life.

The Pillow (Illustration No. 46, Plate IV-A) was used for preservation from sickness and against pain and suffering. It was also worn for the favor of Horus, and was placed with the dead as a protection and to prevent violation of the tomb.

The Lotus (Illustrations No. 47, 48, Plate IV-A) is a symbol with two meanings. Emblematical of the sun in the ancient days of Egypt and typifying light, understanding, fruitfulness, and plenty, it was believed to bring the favors of the god Ra. Later it is described as "the pure lily of the celestial ocean," the symbol of Isis." It became typical of virginity and purity, and having the double virtue of chastity and fecundity it was alike prized for maiden and motherhood.

The Fish talisman (Illustrations Nos. 49, Plate IV-A and 50, Plate IV-B, below) is a symbol of Hathor--who controlled the rising of the Nile--as well as an amulet under the influence of Isis and Horus. It typified the primeval creative principle and was worn for domestic felicity, abundance, and general prosperity.

The Vulture talisman (Illustration No. 51, Plate IV-B, below) was worn to protect from the bites of scorpions, and to attract motherly love and protection of Isis, who assumed the form of a vulture when searching for her son Horus. Thoth, moved by her lamentations, came to earth and gave her words of power, which enabled her to restore Horus to life. For this reason, it was thought that this amulet would endow its wearer with power and wisdom so that he might identify himself with Horus and partake of his good fortune in the fields of eternal bliss.

It is, of course, difficult and futile to speculate as to the extent of the influence these Egyptian amulets and talismans exercised over this ancient people, but in the light of our present knowledge we feel that the religious symbolism they represented, the conditions under which they were made, the faith in their efficacy, and the invocations and "words of power" which in every case were a most essential part of their mysterious composition makes them by far the most interesting of any world culture.

Gnosticism is the name given to a system of religion which came into existence in the Roman empire about the time Christianity was established. It was founded on a philosophy known in Asia Minor centuries previously and apparently based upon Egyptian beliefs, as well as Zendavesta, Buddhism, and the Kabala, with their conception of the perpetual conflict between good and evil.

The name is derived from the Greek Gnosis, meaning knowledge, the gnostics' belief was that the hidden world, with its spirits, intelligences, and various orders of angels, were created by the Almighty, and that the visible matter of creation was an emanation from these powers and forces.

The attributes of the Supreme Being were those of Kabala:--Wisdom--Jeh; prudence--Jehovah; magnificence--El; severity--Elohim; victory and glory--Zaboath; empire--Adonai; the Gnostics also took from the Talmud the planetary princes and the angels under them.

Basilides, the Gnostic priest, taught that God first created

(1) Nous, or mind; from this emanated

(2) Logos, the Word; from this

(3) Phronesis, Intelligence; and from this

(4) Sophia, Wisdom; and from the last

(5) Dynamis, Strength.

The Almighty was known as Abraxas, which signifies in Coptic "the Blessed Name," and was symbolized by a figure, the head of which is that of a cock, the body that of a man, with serpents forming the legs. In his right hand he holds a whip, and on his left arm is a shield. This talisman (see Illustrations Nos. 55, 56, Plate IV-B) is a combination of the five emanations mentioned above: Nous and Logos are expressed by the two serpents, symbols of the inner sense and understanding. The head of the cock represents Phronesis, for foresight and vigilance. The two arms hold the symbols of Sophia and Dynamis, the shield of wisdom and the whip of power, worn for protection from moral and physical ill.

The Gnostics had great faith in the efficacy of sacred names and sigils when engraved on stones as talismans, also in magical symbols derived principally from the Kabala.

One of the most popular inscriptions was Iaw (Jehovah), and in Illustration No. 52, Plate IV-A (second above), this is shown surrounded by the serpent Khnoubis, taken from the Egyptian philosophy, representing the creative principles, and was worn for vitality, understanding, and protection. The seven Greek vowels (Illustration No. 53, Plate IV-B) symbolized the seven heavens, or planets, whose harmony keeps the universe in existence. Each vowel has seven different methods of expression corresponding with a certain force. The correct utterance of these letters and comprehension of the forces was believed to confer supreme power.

Illustration No. 54, Plate IV-B, is an example of the use of magic symbols, the meaning of which has been lost. It is probably a composition of the initial letters of some mystical sigil, enclosed by a serpent and the names of the arch-angels Gabriel, Paniel, Ragauel, Thureiel, Souriel, and Michael. It was worn for health and success; also for protection from all evils, and it is cut in an agate and set in a gold mount.

A figure of a serpent with a lion's head, usually surrounded with a halo, was worn to protect its wearer from heart and chest complaints and to drive away demons.

The mystic Aum, a popular Indian talisman, was also a favorite with the Gnostics, and equally popular was a talisman composed of the vowels Ι Α Ω, repeated to make twelve, this number representing the ineffable name of God, which, according to the Talmud, was only communicated to the most pious of the priesthood. They also adopted from the Egyptians the following gods: Horus, usually represented seated on a Lotus, for fertility; Osiris, usually in the form of a mummified figure, for spiritual attainment; and Isis for motherly qualities.